A legacy of extractive investment as well as low investment and disinvestment in rural and Native communities – by the state and federal governments, financial institutions, philanthropy, and private investors – has hurt rural businesses, people, and places. Some of this has been intentional and purposely discriminatory, dismissing or preventing investments based on geographic location, race, or poverty/wealth status. Some are not intentional but no less damaging – for example, when government funds are allotted by formula to urban places but lower-capacity rural places must compete for what, if anything, is left over. In other cases, resource providers limit how funds can be used, and rural places waste precious effort doing things that are not local priorities.

The result is sporadic, inadequate, and inflexible funding, making it hard for rural doers to plan and meet the true needs and opportunities in their places. Public, private, and philanthropic investors must redesign and retarget funding to provide reliable, accessible, and adequate funding for rural places and businesses to strategically invest in locally determined initiatives and priorities.

building Block Evidence

Evidence suggests this building block is important because experts argue that rural areas’ potential for positive economic “ripple effects” across regions are underestimated—and that investment is critical in areas that steward national food systems, water supplies, and natural recreation areas.1 In addition to regional effects, rural communities have also been critical to national economic recovery from recessions and other economic shocks—despite a history of disinvestment.2

With regard to public capital, tax base size and scope can be a limiting factor in rural areas. For example, in Indiana, rising farmland values since at least 2002 have boosted rural counties’ ability to fund basic services but concentrated the tax burden on fewer individuals, including farmers, as populations decline.3 Some experts note funding for health services may be biased toward serving areas with larger populations; this “structural urbanism” is named as a barrier to rural areas receiving adequate public investment.4 Recommended solutions include a “rural audit” of criteria used in federal community and economic development programs to address barriers to entry for rural areas.5

With regard to private capital, researchers note historic underinvestment in rural areas by venture capital firms and recommend investment via community development venture capital (CDVC) firms, with the caution that fund management teams must ensure positive returns.6 CDVC investments tend to be in rural (nonmetro) areas, “in industries outside the venture capital mainstream,” and their profitability is unclear.7 However, CDVC activity may increase traditional venture capital activity, which is a benefit.7 Nearness to cities may also mean greater access to capital and employment opportunities for residents of adjacent rural counties.8

More than 1,000 Community Development Financial Institutions operate across the US, with almost 30% of CDFIs receiving grants serving rural markets.9 CDFIs can expand economic opportunity for communities excluded from mainstream lending and other financial services,10 though increased CDFI lending is needed in rural areas.11 In rural and urban settings, Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs) serving Native communities successfully administer business, home, and personal loans, in addition to providing technical assistance and training.12 Responding to the “disconnect between tribal communities and traditional sources of development capital such as banks, credit unions, and other commercial lenders,” experts have also proposed the creation of a Tribally Chartered Bank (TCB), with regulation by an independent, tribally appointed governing body.13

With regard to philanthropic investment, research shows that rural communities receive fewer grants from foundations than what may be needed, given their share of the US population, with less value per capita compared to metro counties—and that even among rural recipients, distribution is uneven.14 Compared with grants received by urban applicants, rural organizations are more likely to receive grants for higher education, environmental concerns, and recreation and leisure; grants are also more likely to support direct investments in physical and human capital than financial or intellectual capital.14 The Walsh Center for Rural Health Analysis has strategies for rural programs to build partnerships with philanthropies.15 Recent research by the First Nations Development Institute also finds that Native-led nonprofit organizations receive a tiny percent (0.23) of US philanthropic funds, a disproportionately low share of funding for Native populations, which are approximately two percent of the overall US population;16 communities are also among those of “greatest need”.17

- LISC-Anarde 2019

- EIG-2016

- DeBoer 2020

- Probst 2019

- Brookings-Pipa 2020

- Moncrief 2006

- Kovner 2015

- Brookings-Arnosti 2018

- CDFI Coalition 2019

- Urban-Theodos 2020

- Urban-Theodos 2017

- Native Nations Institute 2016

- Guedel 2016

- USDA-Pender 2015

- NORC-Philanthropies 2019

- NCAI-Demographics

- First Nations Development Institute 2018

Curated Resources

Unlocking Potential: Regional Place-Based Investments

Aspen CSG Co-Executive Director Chris Estes shares why place-based investments are critical at the White House Summit on Capital Support for Place-Based Economic Development.

Funding Rural Futures: A Call to Action

What it will take to make more flexible and responsive funding available to rural development organizations serving low-income and persistent poverty rural regions?

Mapping a New Terrain: Call to Action

As new rural outdoor recreation economies take root, we can meet this moment by improving how we do outdoor recreation development to better support rural families, businesses, and workers, create more sustainable and equitable economic systems, and improve local health and wellbeing.

Challenging Current Rural Funding Strategies

In an op-ed for Daily Yonder, Bonita Robertson-Hardy of the Community Strategies Group writes on how rural communities, funders, and other stakeholders’ approach to economic development can mean the difference between success and stagnation.

Translating Federal Opportunities into Local Resources

This short case study has insights and tips on how rural communities with limited staffing and resources can understand, prepare for, and compete for finite federal funds.

Securing Capital for Rural Prosperity

This third in the Thrive Rural Field Perspectives series offers a call to action to restructure and reorient public, private…

Try This at Home: Create a Family Lifeline to Weather Financial Storms

Could we construct a way for an investor, a bank, and a philanthropy in our community to team up to make consumer loans to families in distress? In doing so, could we create a blueprint that communities could also use in the wake of a natural disaster or other community crisis?

Building Capacity in Rural & Indigenous Communities

Insights and learnings from rural practitioners on how organizational capacity and technical assistance can be carefully and intentionally strengthened to grow economies, health, and livelihoods for each and every person in their regions.

Field Items

PHILANTHROPY MUST CHANGE SO COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT CAN KEEP CHANGING FOR THE BETTER

Inside Philanthropy

Foundations should build on their success in supporting multisector, multifield collaborations to establish a consensus on development that centers race and people.

GIVING FOR RURAL COMMUNITIES

Inside Philanthropy

Explore the foundations, major donors, and corporations that are making grants to nonprofits for rural communities.

PARTNERS FOR RURAL TRANSFORMATION RESOURCES

Partners for Rural Transformation

Resources and tools from the Partners for Rural Transformation, a coalition of CDFI’s working in rural persistent poverty regions.

ACCESS TO CAPITAL AND CREDIT IN NATIVE COMMUNITIES

The University of Arizona Native Nations Institute

This report from Native Nations Institute tells a story of American Indians’, Alaska Natives’, and Native Hawaiians’ determination, progress, and hope for improved financial access and economic stability—and of their desire to build Native Communities that prosper for generations to come.

THE “RIPPLE EFFECT” OF INVESTING IN RURAL AMERICA

Local Initiatives Support Corporation

Projects may not touch the numbers of people or generate the returns of urban investments, but their effects are every bit as important, and ripple far and wide through the small, intricately connected networks of rural life.

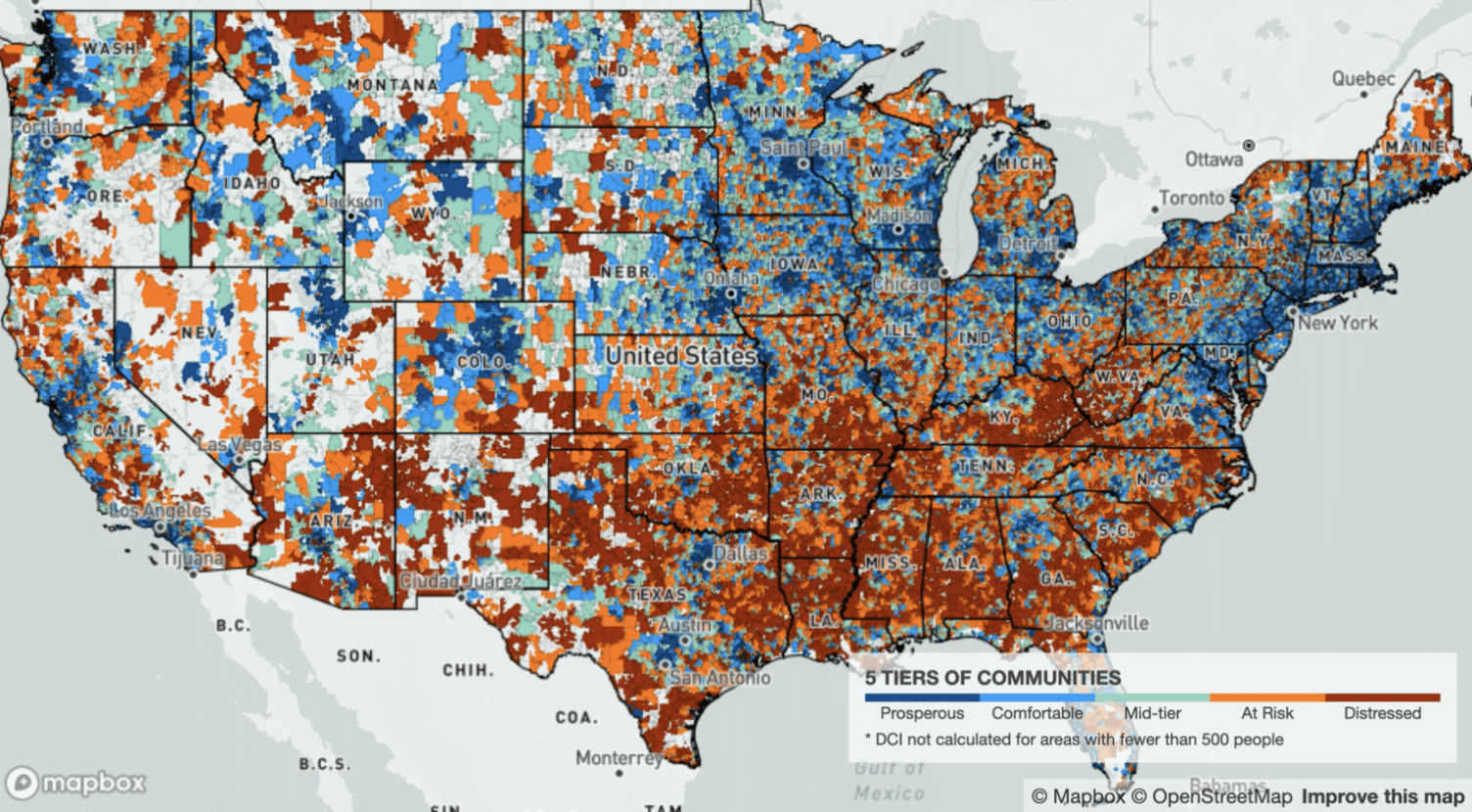

WHICH THINK TANKS THINK ABOUT RURAL AMERICA?

The Daily Yonder

Economic Innovation Group think tank offers tools that introduce “geographic inequality” into the national conversation and bring rural America’s economic distress to the forefront.

PATHWAYS TO SECURING RURAL FEDERAL FUNDING

The Ford Family Foundation

The Ford Family Foundation and Sequoia Consulting’s research analyzes the causes of inequitable access to public funds and develops recommendations to access public funding streams from federal and state governments.

HOW CONSISTENT CAPITAL FLOW CAN SAVE RURAL AMERICA

Partners for Rural Transformation

With current and anticipated funding already accounted for, take a look at how the Partners maximize capital flow to improve the livelihood of their service areas.

CDFI LOCATOR

Opportunity Finance Network

Use the search filters to locate and learn more about Opportunity Finance Network (OFN) member CDFIs based in rural, urban, and Native communities across America.

PARTICIPATORY INVESTING TOOLKIT

Common Future

Explore Common Future’s playbook for power-shifting in philanthropic investment.

EQUITABLE COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT

Resources from RWJF on transforming neighborhoods to improve health and wellbeing.

GET HELP APPLYING FOR FEDERAL FUNDING

Just Transition Fund

The Federal Access Center is a one-stop resource hub to help coal communities secure public funding for local economic solutions.

We see the framework as a living document, which necessarily must evolve over time, and we seek to expand the collective ownership of the Thrive Rural Framework among rural equity, opportunity, health, and prosperity ecosystem actors. Please share your insights with us about things the framework is missing or ways it should change.