Rural communities, like any community, do better when more of the people who live and work there do better. Too many rural places in the United States are home to persistent and deep poverty, especially (but not only) among people of color and immigrants, due to the legacy of historic and ongoing discriminatory economic development and resource exploitation.

Communities must first detect and acknowledge the local policy and program design, regulatory, and behavioral barriers preventing more people from getting ahead. Going forward, they must intentionally ensure that local individuals, families, and stakeholders who are striving but not thriving are included in the decision-making and in the benefits of economic and civic development efforts to increase both equity and prosperity.

BUILDING BLOCK EVIDENCE

Evidence suggests this building block is important because diverse leadership and inclusive processes can be associated with positive impacts on well-being and equity considerations in the work, though more research is needed. Evidence-building for equity-centered leadership includes studies of outcomes of diversity and inclusion practices of leadership entities, public participation processes in multiple fields, and community groups that push formal decision-making bodies to center equity. The composition and diversity of organizational leadership and boards illustrates this concept. Nonprofit boards in the US tend to be older, white, and male.1 While the evidence base connecting the diversity of boards and equity-related outcomes is not robust, studies find board diversity important for a range of outcomes, including board performance and legitimacy with the community.2

Leaders can center equity via robust community engagement. Reviews of public participation processes in which community members have a say in the policies and programs that impact their lives reveal that there is a wide variety of engagement and decision-making power, ranging from performative engagement to meaningful levels of community power and co-creation. Notably, research also indicates that poorly designed or implemented public participation approaches can negatively impact participants. It is not just participation that is important but meaningful participation in organizational processes that are inclusive, accessible and supportive.3

Systematic reviews of the evidence conclude that public health interventions using community engagement positively impact health behaviors, health consequences, community members’ sense of self-efficacy, and perceived social support outcomes.4 These reviews also identify factors for successful community engagement, such as having accessible infrastructure in place for connecting and communicating with community members, an open attitude towards and training for community engagement, seeing community members as partners, and community members feeling ownership in the process.3,5,6 Robust research on models of community engagement for health improvement of marginalized populations show positive impacts on health behaviors, public health planning, health service access, and health literacy. Power-sharing, collaborative partnerships, bidirectional learning, and incorporating voice and agency were key community engagement components for positive health outcomes.7

Other developmental and planning processes similarly put humans or community members at the center of the planning process and goals. Native nation-building is the foundation for effective regional rural development for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations. Successful strategies embrace both tribal sovereignty and relationship building between Native communities and their non-Native neighbors.8 In the workforce development field, experts suggest that improving employment opportunities in rural areas requires redesigning workforce development systems and approaches that recognize the challenges and aspirations of rural communities, workers, and jobseekers.9-11 Expert opinion also suggests that designing community and economic development efforts for rural vitality requires fostering rural leaders through programs that elevate inclusion, resilience, and collaboration12 (see also, G: Prepare Action-able Leadership). More recently, human-centered design has emerged from the design field and social sector as a way to apply design principles to social issues13 and in public health initiatives focused on a specific product or concept.14,15

Curated REsources

Mapping a New Terrain: Call to Action

As new rural outdoor recreation economies take root, we can meet this moment by improving how we do outdoor recreation development to better support rural families, businesses, and workers, create more sustainable and equitable economic systems, and improve local health and wellbeing.

Using Relational Leadership to Build Power Together

This short case study has insights and tips on how communities that have been historically and systematically excluded can develop authentic and effective leadership that builds power to challenge the status quo.

Translating Federal Opportunities into Local Resources

This short case study has insights and tips on how rural communities with limited staffing and resources can understand, prepare for, and compete for finite federal funds.

Broadening Authentic Leadership: Student Action with Farmworkers

This short case study has insights and suggestions for how rural-serving organizations can effectively welcome and truly empower leaders from all backgrounds.

Measure Up: A Call to Action

Today, we have a generational opportunity to strengthen prosperity and equity in communities and Native nations across the rural United…

Defining Rural Development Success

There are no easy solutions for the many challenges that rural Americans face, but it’s clear that rural communities themselves…

Disaster Planning and Rural Resilience

Flooding, tornadoes, drought, wildfire, and other extreme weather events cause major disruption and damage wherever they occur and have potential…

Native Nation Building: It Helps Rural America Thrive

Native nations and rural communities, working side-by-side and together, can strengthen the potential for thriving rural regions.

Field Items

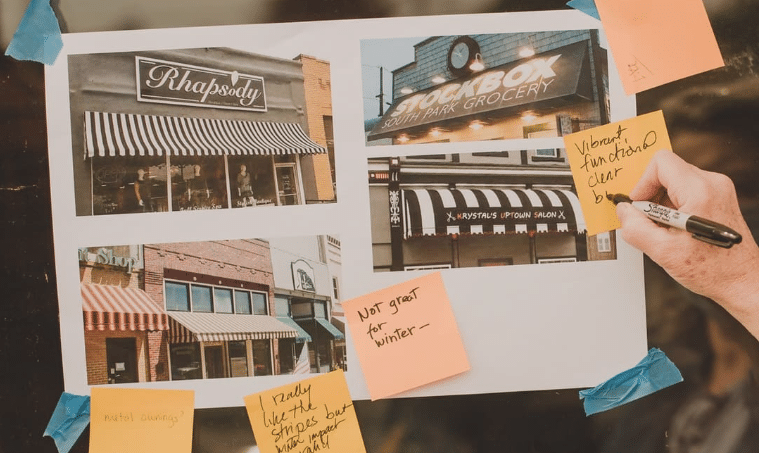

Citizens’ Institute on Rural Design

CIRD empowers local citizens to use their unique artistic and cultural resources to guide local development and shape the future design of their communities.

Rural America Placemaking Toolkit

The Rural America Placemaking Toolkit is a resource guide to showcase a variety of placemaking activities, projects, and success stories…

FAMILY-CENTERED COACHING

Family-Centered Coaching

Family-Centered Coaching Toolkits are strategies, tools, and resources to work holistically with families as they strive to reach their goals.

2-GEN TOOLBOX

Ascend (Aspen Institute)

The updated 2Gen Toolbox includes more than 300 resources from key 2Gen leaders and consultants, gathered by Karen Murrell (Higher Heights Consulting), Aspen CSG and Ascend.

DESIGN THINKING FOR RURAL INNOVATION

SUNY Geneseo

Design thinking, or Human Centered Design, is a process for creative problem solving used by various sectors that puts people at the center of the design process.

Housing Justice Narrative Toolkit

At Aspen CSG, we recognize that how we tell stories about housing matters as much as the facts we share….

MEETING LEADERS WHERE THEY ARE

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

Rural Development Initiatives (RDI) shares lessons from their Rural Community Leadership Program.

Reimagine Appalachia Resources

ReImagine Appalachia

ReImagine Appalachia’s whitepapers show that federal investments in the people, communities and infrastructure of Appalachia can work to revitalize the region.

We see the framework as a living document, which necessarily must evolve over time, and we seek to expand the collective ownership of the Thrive Rural Framework among rural equity, opportunity, health, and prosperity ecosystem actors. Please share your insights with us about things the framework is missing or ways it should change.