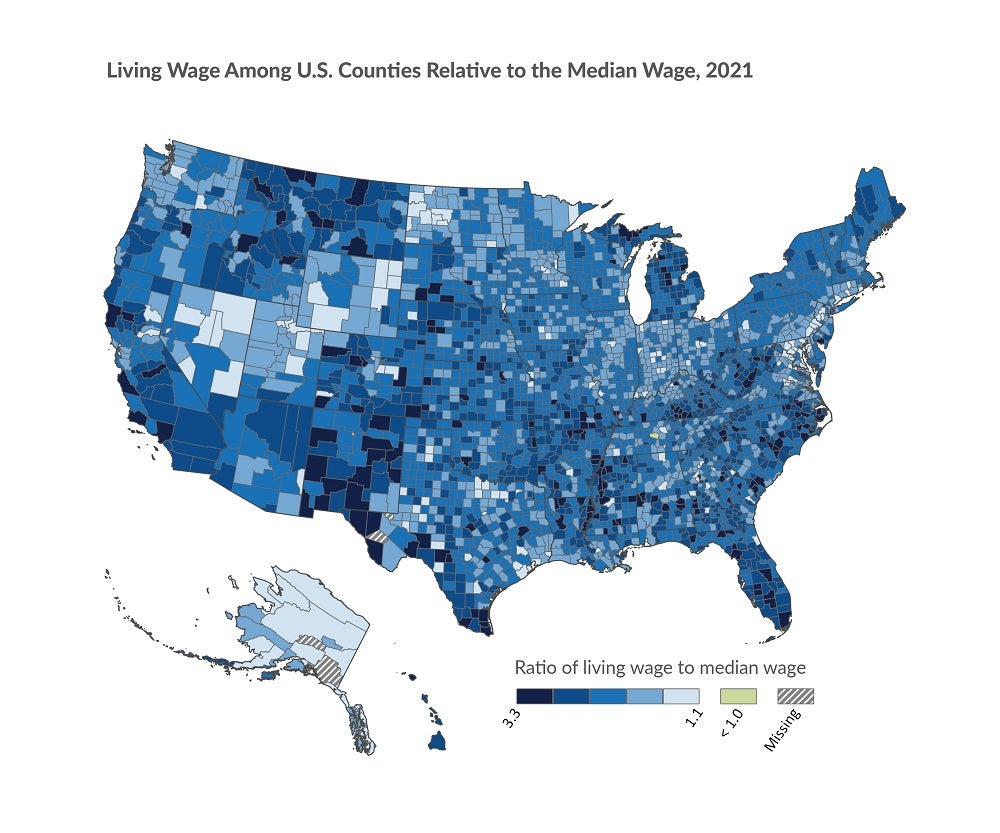

One large challenge in devising strategies and improving outcomes for rural and Native communities is the lack of relevant data at meaningful rural geographic levels that can allow for both analyzing the “starting point” situation in a rural community and measuring progress from that starting point. Confounding that situation is the fact that dozens (or perhaps scores) of definitions of “rural” are used by federal and state governments, and the related datasets do not or cannot provide useful information on elements important to rural-level planning and analysis. This situation additionally challenges any rural community’s or region’s ability to measure what it rightfully defines for itself as success or progress.

Governments must develop a better sub-county-level data collection system for a fuller range of the demographic, economic, social, and infrastructure factors in rural communities. This is critical to understanding the inequities in investment and prosperity for rural and Native communities, businesses, and people – and to drive toward a more equitable alignment of rural resources and support.

Building block EVIDENCE

Evidence suggests this building block is important because high-quality data is an essential part of evidence-based policymaking at the local, state, and federal levels.1 Native nations also seek to build, control, and use high-functioning data systems, as emphasized in movements for Indigenous data sovereignty and data governance.2

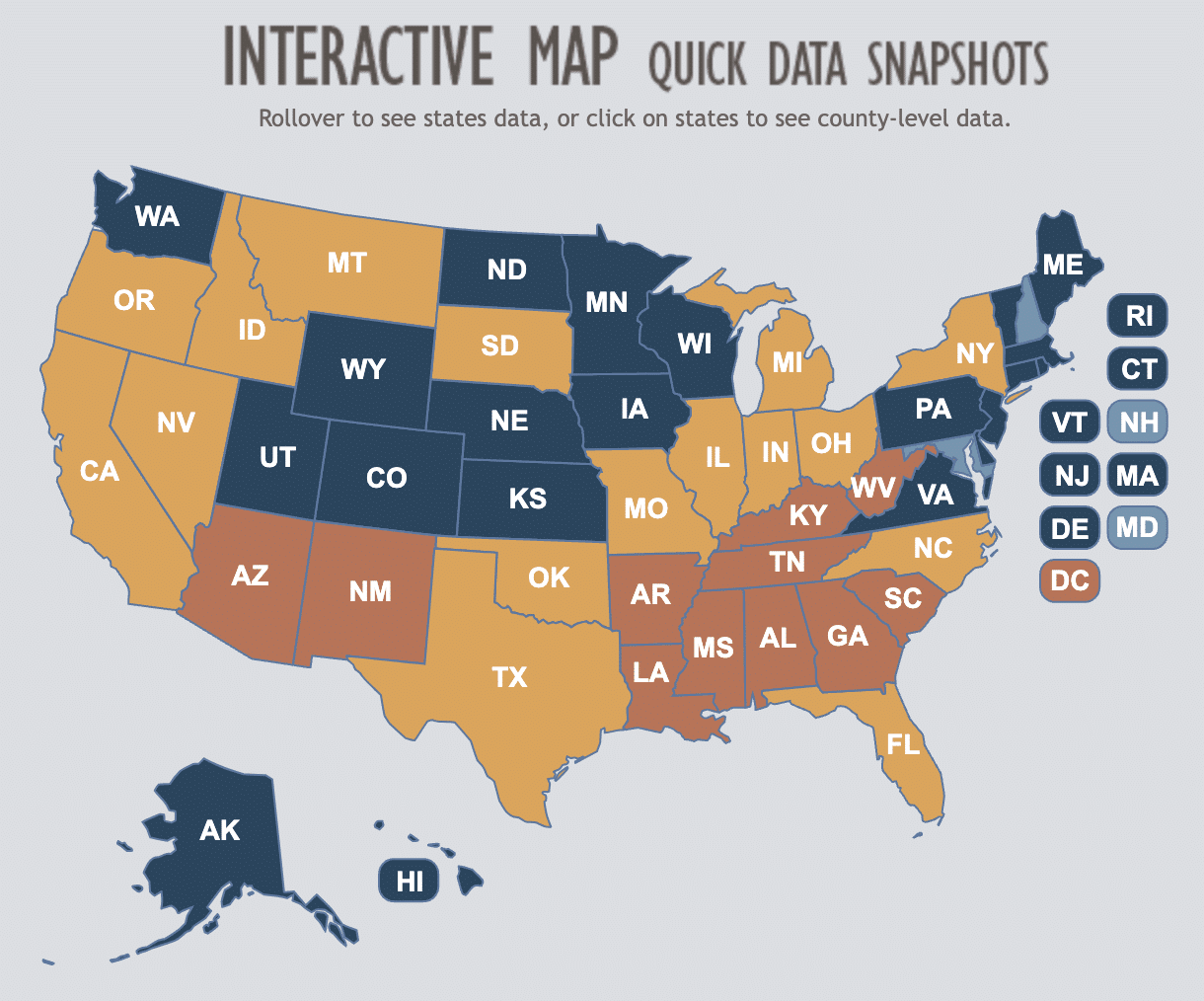

A range of rural-related data is organized by the federal Interagency Council on Agricultural and Rural Statistics (ICARS),3 including data from the US Census Bureau.4 For more, see US Census ACS-Rural 2020.5 For county-level data, the US Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service offers typology codes that reflect economic and social characteristics to “provide policy-relevant information about diverse county conditions to policymakers, public officials, and researchers”.6 Given that nonmetro counties include rural towns with fewer than 2,500 people and urban areas approaching 50,000 people,7 these codes provide useful layers of detail. Experts note that a persistent problem in rural census-level data collection is protecting individuals’ privacy while meeting needs for data completeness.8 Suggested improvements from the field include a broader range of data sources and, where appropriate, consolidation of data into richer datasets,9 which aligns with best practices in data governance. Best practices include managing security and privacy risks; promoting the development of policy and legal frameworks to enable data use; and “harmonizing data exchange formats” so data can be pooled to maximize its utility and quality.10

Research suggests that so-called “big data” can inform better decision- and policy-making, with good data governance practices.10 Big data refers to emerging data sets with greater volume, variety, and velocity (meaning more observations, from more sources, often with real-time collection and analysis); examples include electronic medical records (EMR) and electronic health records (EHR), social media and online data, spatial/geographic data, and data from the physical environment.10 Such data has applications across sectors and settings. For public health practitioners, traditional methods of disease monitoring and health promotion in communities are complemented by high-quality analysis of this big data.10

Experts in Indigenous data governance note that “extensive data are collected about Indigenous peoples and nations, but rarely by or for Indigenous peoples’ and nations’ purposes”.11,12 Such data is often inaccurate and irrelevant for tribal governance needs.13,14 Scholars emphasize the value of data systems that privilege Indigenous worldviews, noting that “strong tribal data systems” are critical to Native nations’ “foundational capacity…to make and implement strategic decisions about their own affairs”.12,13,15-17 For more, see the Collaboratory for Indigenous Data Governance.18 The work of the Indigenous Observation Network in monitoring water quality in the Yukon River watershed is an example of Indigenous-led data collection and governance, involving First Nations and Alaska Native Tribes.19,20 Twelve Tribal Epidemiology Centers (TECs), funded in part by the CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and Indian Health Service (IHS),21 also support this capacity-building. As of 2010, TECs are designated as Public Health authorities, which grants them access to IHS data.22 The TECs’ functions include data collection, monitoring, and analysis—including reclassification of state-level data to more accurately represent Tribal Nations23—and overall evaluation of systems impacting the improvement of Indian health, including data systems.23 The TECs are “community-driven,” meaning formal direction is provided by the populations served.24

- Pew-MacArthur 2014

- Russo Carroll 2019

- USDA-ICARS

- USDA-Rural Data

- US Census ACS-Rural 2020

- USDA ERS-Typology

- USDA ERS-Classification

- Urban-Bowen 2020

- Urban-Payton 2020

- OECD Data-Gall 2019

- Walter 2018

- United Nations 2018 in Russo Carroll 2019

- Rodriguez-Lonebear 2016

- Rainie et al. 2017c in Russo Carroll 2019

- Jorgensen 2007

- Kukutai and Taylor 2016

- Rainie et al. 2017c

- Collaboratory for Indigenous Data Governance

- Indigenous Observation Network

- Wilson 2018

- TEC

- Cresci 2019

- Duke 2019

- Finkbonner 2019

Curated Resources

Measure Up: A Call to Action

Today, we have a generational opportunity to strengthen prosperity and equity in communities and Native nations across the rural United…

Weaving Health Equity and Rural Development Through Data

Learnings, insights, and resources to better understand where progress is needed on weaving health equity and rural development and what wins we all can celebrate.

In Search of Good Rural Data: Measuring Rural Prosperity

Economic and demographic data drive research, policy development, distribution of government resources, and private investment decisions. But many of the…

Building Trust With Community-Based Participatory Research

This research brief explores how rural MSIs and approaches to community-based participatory research can be used to better understand MSIs’ nature and practices.

Defining Rural Development Success

There are no easy solutions for the many challenges that rural Americans face, but it’s clear that rural communities themselves…

Building Better Fundamentals for Rural Progress

Sector-specific solutions dominate rural policy. We often hear about rural health, rural water, rural housing, broadband, agriculture. These are pieces…

Field Items

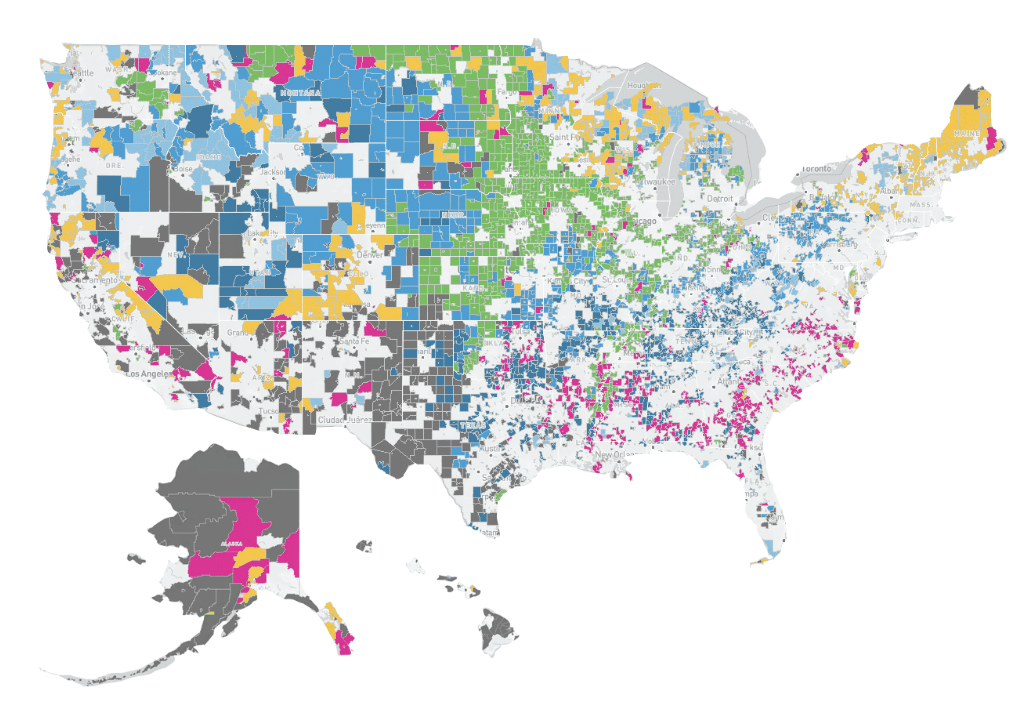

HEADWATERS CAPACITY MAP

Headwaters Economics

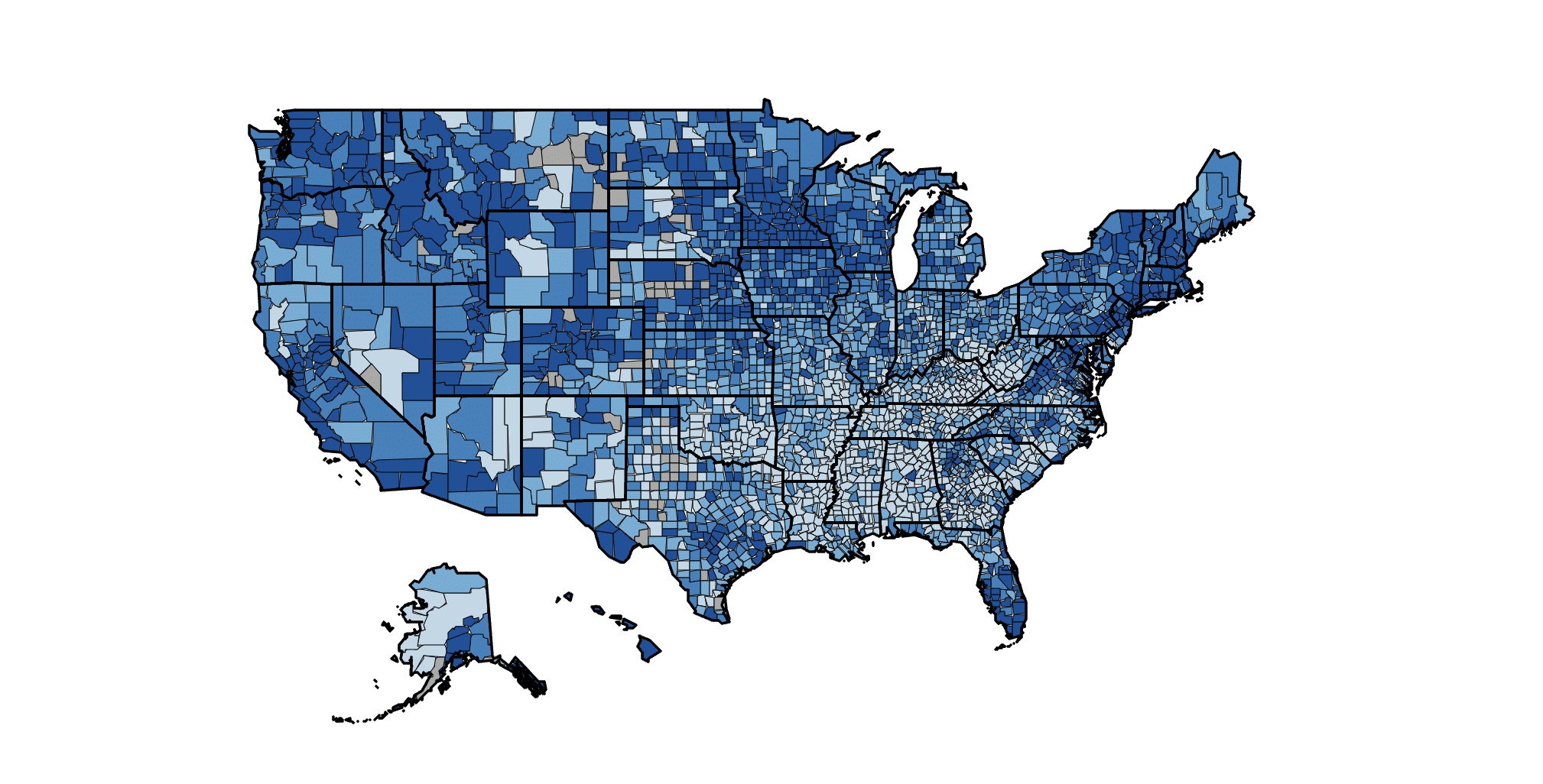

A Rural Capacity Map: To help identify communities where investments in staffing and expertise are needed to support infrastructure and climate resilience projects.

2023 County Health Rankings Analysis

County Health Rankings & Roadmaps (CHR&R) brings actionable data, evidence, guidance and stories to support community-led efforts to grow community…

The Rural Aperture Project – Aspen CSG

The Rural Aperture Project from the Center on Rural Innovation is intended to provide all those advancing rural prosperity — from practitioners…

THE RURAL DATA PORTAL

Rural Data Portal

HAC’s Rural Data Portal is a simple, easy to use, on-line resource that provides essential information on the social, economic, and housing characteristics of communities in the United States.

INDIGENOUS DATA SOVEREIGNTY & GOVERNANCE

The University of Arizona Native Nations Institute

Resources from the University of Arizona Native Nations Institute on indigenous data sovereignty.

COLLABORATORY FOR INDIGENOUS DATA GOVERNANCE

Collaboratory for Indigenous Data Governance

The Collaboratory for Indigenous Data Governance develops research, policy, and practice innovations for Indigenous data sovereignty.

NCAI POLICY RESEARCH

NCAI Policy Research Center

Policy and data sovereignty tools from the National Congress of American Indians.

REENVISIONING RURAL AMERICA

Urban Institute

By illustrating the varied realities of rural communities, this dashboard allows local, state, and federal policymakers; practitioners; and investors to see the diversity of rural America and to better invest in its full potential.

COUNTY GOVERNANCE PROJECT

National Association of Counties

Use this database to compare information across all 48 states with county governments. Select one of the four categories at the top, then dig into specific datasets, maps and charts within each category. In any data table, use the search bar at the top to isolate similar states based on specific data points or click on an indicator name to sort the data.

FEDERAL DATA ON RURAL CLEARINGHOUSE

USDA Economic Research Service

This listing provides a summary of the major Federal sources of statistical data used to analyze rural areas. The data sources are categorized by their content, time period, as well as their geographic coverage.

RURAL HEALTH MAPPING TOOL

NORC at the University of Chicago

This tool allows CDC, other researchers, community organizations, local policymakers, and the public to create county-level maps illustrating the relationship between COVID-19 vaccination coverage rates and other health outcomes, socio-demographic, and economic variables across all counties of the United States. Insights derived from this tool can be used to target resources and interventions, and inform efforts, particularly in rural areas, related to vaccination coverage rates.

RURAL COMMUNITIES NEED BETTER DATA

Urban Institute

Urban Institute scanned more than 20 data sources on rural prosperity and spoke with a range of rural researchers and practitioners. This blog shares how rural data fall short.

We see the framework as a living document, which necessarily must evolve over time, and we seek to expand the collective ownership of the Thrive Rural Framework among rural equity, opportunity, health, and prosperity ecosystem actors. Please share your insights with us about things the framework is missing or ways it should change.