A Q&A with Ta Enos

Tataboline “Ta” Enos believes fair and just rural development is rooted in asset-based approaches, with rural residents best positioned to shape their own futures.

Putting this theory into action, Ta founded and became CEO of the PA Wilds Center for Entrepreneurship, Inc., a nonprofit that champions place-based entrepreneurship, outdoor recreation, and creative-sector growth across north-central Pennsylvania. The organization weaves together stewardship and community development to strengthen local economies.

As a long-time Aspen CSG collaborator, Ta brings deep insight into building collaborative networks across sectors ranging from small businesses and artisans to public land managers and regional and state advocates.

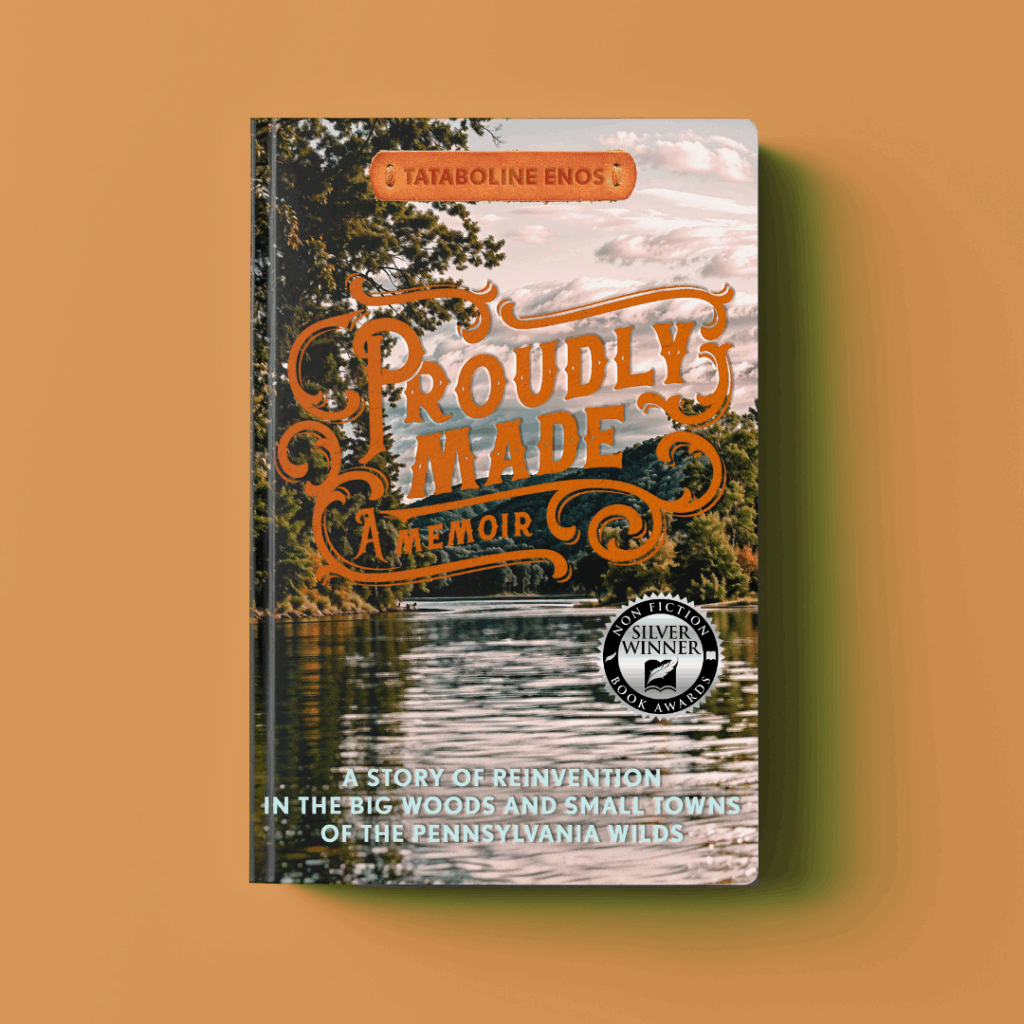

Ta is also the author of a recently released memoir, Proudly Made: A Story of Reinvention in the Big Woods and Small Towns of the Pennsylvania Wilds. Ta’s book serves as an important counterweight to incomplete portrayals of rural communities often shown in the media.

We sat down with Ta to discuss how her rural background shapes her work, the importance of working as a Rural Development Hub, and how we can keep strengthening accurate rural narratives.

Don’t miss Aspen CSG’s mentions on pages 100, 150, and 203 of Proudly Made! Ta Enos shares how Aspen CSG’s Rural Development Hubs model helped clarify PA Wilds’ regional, cross-sector approach and illuminate both the challenges and opportunities of operating as a Hub.

You grew up in the Pennsylvania Wilds, and your family has lived there for four generations. How has your personal connection to the region shaped your approach to rural development?

Growing up here gave me a deep respect for nature and the outdoors, for rural culture and people working with their hands, and for how family, community, creativity, and a sense of place can ground a person. Those experiences are baked into my vision for rural development. And by that I mean I believe that any development approach needs to start with respect for what has come before and involve stewardship for local culture and place while you innovate and change.

Many rural places face stacked challenges that come from decades of disinvestment and extractive approaches, and mega forces like digitization, urban migration, and globalization. It’s been a story of industry contraction, empty storefronts, schools and health centers closing, population decline, young people losing hope.

I’ve lived that experience. And it’s led me to ask: How do we take some of these systems and narratives that have vacuumed so much wealth, power, and agency out of rural communities and turn them on their head to start pulling that back in? How do we make rural economies more inclusive, so there’s more pathways for success?

In addition, I share in Proudly Made that I didn’t have much growing up. I was raised by a single mom who herself came from a poor working-class family. Those experiences have also shaped my vision for rural development.

In your book, you write how Aspen CSG’s Rural Development Hub model strongly resonated with you. How has working as a Hub influenced the way you approach collaboration and systems change?

I have this whole scene in my book about the first time I discovered the Rural Development Hub model and how blown away I was. I didn’t know anything about the Aspen CSG then, and I just felt completely validated and re-energized, like, this group gets it. They SEE us. Our opportunities, our challenges, the value of supporting organizations like us, the difference we’re making in some of America’s most forgotten, hardest-to-reach places.

I’ve since participated in several Aspen CSG studies, so now I get why your team is so often spot on – because in addition to rigorous academic research, your methods include feedback loops with all these practitioners in the field. I’m a complete geek for your studies now, because they are grounded that way.

Speaking more directly to your question, because we were already working as a Hub, it was less about influencing the way we approach collaboration and systems change, as giving us language and academic sourcing to finally describe, validate, and build trust in it. That’s been huge in helping us attract new investment.

In many rural places, trust wasn’t just lost—it was actively undermined by decades of disinvestment and harmful policies. Building that trust back takes time and purposeful work. What approaches have you found most effective for fostering trust across such a diverse network of partners?

Rural communities have been through so much at this point, and many are so cut to the bone that new ideas or approaches are often met with what I’d describe as a healthy skepticism.

I write in Proudly Made about how the PA Wilds work went through this when it started 20 years ago. The state was a big actor in our regional work – they essentially launched it and got everyone to the table. Parts of the initiative, in the very beginning, were very top-down. That did not go over well here.

So there was this moment early on where local communities really pushed back. And instead of being met with ego or lip service or whatever, the state listened. And there was this intentional reset. More inclusive structures were developed to allow rural communities to help shape and guide things. So that was a huge trust-building moment for us. From there it was, will the state follow through on its promises? And it did, and that also built a lot of trust.

A big actor can help get people to the table in a new approach, but local ownership is key to making it last. We successfully made that transition, with our state partners still by our side. By then, partners had developed multiple networks that helped shape and influence the work – one centered with our region’s county governments, another made up of rural small businesses, and eventually, PA Wilds Center, a backbone nonprofit with a volunteer Board of Directors and staff to house and steward these and other frameworks. All of that helped build trust.

More personally, I write in Proudly Made about how people vouched for me behind the scenes as I founded the PA Wilds Center. That kind of social capital is huge to getting liftoff in rural communities. From my personal experience, I’d say in new relationships, everything matters –who the messenger is, that they show up in person, the language they use, that they listen, are transparent, how they empower others to be part of a process. No matter what stage you are at, I think the throughline is: show up, be real, be inclusive, follow through.

Don’t be afraid to put yourself out there— vulnerability takes courage, and people respond to that. When you screw up, own it. Change and uncertainty can be hard to deal with, even when they consider place and tradition as you innovate. Create enough space and grace for people to be “againsters” at first and to come around to ideas later, when they feel more comfortable. I find they often do.

As communities grow, shared wealth building reduces displacement and ensures residents retain personal assets. Outdoor recreation is a major economic driver in the PA Wilds, Can you tell us about the strategies you use to build and keep wealth in the region?

Some really important decisions and approaches happened before my time, but I researched them for my book because I’m just so grateful local leaders had the foresight to prioritize them. One – which came from local communities and was later championed by state and federal partners – was to have a key focus on growing and supporting local entrepreneurs and small businesses. This, in my mind, is one of the best buffers against tourism becoming extractive. The more you can direct visitor and investor dollars toward hyper-local businesses and nonprofits, the bigger the return, because money spent locally stays in the community longer, supporting jobs, families, other businesses, community giving, stewardship, etc.

I write in my book how we established a free rural value chain network – again, shaped by Aspen CSG’s research – which today has more than 700 members to meet market demand and drive wealth back into rural communities through small businesses and nonprofits. Once part of the network, members can connect to financing and other small business service providers (we intentionally try not to duplicate services being offered by partner organizations).

Almost all of our contracts – for HR services, social media services, content generation, legal, etc – are local companies participating in our value chain. We encourage business-to-business sales, partner with other organizations to do specialized programming like business plan competitions, and advocate for more innovative capital funds to support small businesses.

We’ve established a licensing program to allow rural small businesses to use the PA Wilds trademarked logo to bring new products, like souvenirs, to market. We also help market service-sector businesses through our regional visitor site, pawilds.com.

Over the last few years, we’ve added brick-and-mortar and digital marketplaces to our ecosystem to help rural makers and producers get their products to market with the added marketing punch of the regional brand. More than $3 million of rural products have now been sold across these platforms, driving wealth back into rural communities through small businesses.

We’ve spent the last 18 months researching how we strengthen these underlying systems even more through a placemaking technology platform, steeped in nonprofit principles, that any rural landscape – including us – can subscribe to accelerate learning and increase value capture by working together. We are pitching that project now.

You’ve said, “Narratives about a place are powerful things. Too often in rural America, and definitely in Appalachia, they are told by people from outside and through a lens that is often negative.” You’ve used your book to share accurate stories of your region. How can other rural leaders help shift these narratives?

In the Wilds, we have this saying, “Be The They.” You know those situations where things aren’t going great, and you have people on the sidelines pointing fingers, They ought to do this, and They ought to do that. In my experience, the communities where positive change is happening it’s because someone, or a group of people, decided to “Be The They.” To be the ones to take the first step, even though it may feel small and insignificant and get ridiculed. To refuse to accept disinvestment, and to continue showing up until that effort and courage becomes contagious. Because eventually, it will.

Also, don’t minimize your wins – level them up. Several years ago, I read a headline from an article published by the Kauffman Foundation that has stuck with me: “After generations of disinvestment, rural America might be the most innovative place in the US.” It was about the Heartland, but could well have been about the PA Wilds. My point being – rural communities are filled with outside-the-box thinkers and doers. Identify and celebrate local innovation and stewardship efforts and the people behind them, and connect these wins publicly to larger strategies or trends that apply to your place.

Finally, tell your story and keep telling it. Invest in the tools and people who can do this authentically and well, including using different voices and images from your place.