Reliable field resources, including many produced by Aspen CSG, center asset-framing as primarily a household-level and local issue. For example, our Thrive Rural Framework has specific building blocks on Strengthening Local Ownership and Influence and Build from Current Assets to increase wellbeing and equity outcomes within the framework’s Local Level Theory of Change.

But the framework is designed to spur thinking simultaneously on local and systems levels, so what is the systems-level responsibility for acting on assets? Historically this would fall under capital access within the Ready Rural Capital Access and Flow building block. Local, regional, and state groups working to address redlining, predatory lending, and other forms of structural barriers to capital first advocated and challenged lenders in the community and region for better and fair lending. However, through bank mergers and the collapse of the Savings and Loan industry, the number of banks shrank, and most of the headquarters moved to a few large cities. This led to more systemic efforts in legislative efforts at the national and state level, as well as pressure for more consistent enforcement of the Community Reinvestment Act by federal regulators.

However, there is more to consider than just private sector and CDFI (Community Development Financial Institution) lending when focusing on asset building.

Viewing the barriers of structural discrimination more broadly around race, place, and class and applying them to federal and state funding that impact rural prosperity is an important strategy that supports equitable rural prosperity.

Activities within the field suggest that recognition of the importance of intentional, coordinated action at the systems and local levels is growing. Take, for instance, a recently released framework for just and equitable transition in coal communities that argues top-down federal programs need to coordinate and collaborate with regional stakeholders to reclaim and redevelop assets like shuttered coal mines and power plants. Doing asset-based work like this would require actors at all levels to challenge their historical biases and change the narrative of what assets look like within rural contexts.

Asset-Based Learnings and Resources from the Field

Focusing on family and community assets provides opportunities for actors at all levels to address inequity and historical discrimination

- Asset-based development is a strategic way to include rural Indigenous communities who have been disadvantaged through geographic, racial, and/or class discrimination.

- Noel Andrés Poyo suggests that inclusive rural development unlocks opportunities for people and communities that have been historically marginalized, and recent Aspen CSG work has shown this to be true for refugee and immigrant populations.

- Outside asset strategies resonate with Mark Little’s piece in the recent Thrive Rural Field Perspective brief What (and Who) Counts?. Little explains how increasing financial and political power is the route to rural Indigenous, Latino, and Black communities achieving success on their terms.

- Achieving control of financial and capital assets is the theme of a recent piece by Rodney Foxworth at Common Futures (formerly BALLE). The article explores how Common Futures established and resourced a board-designated fund that put power directly in the hands of community organizations (like Native Women Lead).

- The Southern African American Land Retention Network (SFLR) works with rural African American landowning families to reframe land ownership as an asset, rather than a liability and provides legal and technical advice to unlock family land as a financial asset.

- For Native nations and Indigenous people, the land is inextricably linked to spiritual and cultural identity. The LandBack movement and recent high-profile examples of ancestral land being returned to or purchased by Native nations should be seen, in part, as asset-building (for examples, see Yurok, Rappahanock, and Onondaga). Regaining ownership of stolen ancestral and sacred land is a big step in building and rebuilding cultural and natural assets, as well as forward movement in restoring the full dignity and wellbeing of Indigenous communities.

- Scientists are learning that lands managed with traditional ecological knowledge provide multiple benefits for all, including increased biological diversity and mitigating climate change and wildfire risk. And with the increasing adoption of carbon markets and the use of offsetting as a technique by systems-level actors to reduce carbon footprints, natural landscapes are poised to provide financial assets as well.

How systems-level actors measure local assets matters

- Accurate measurement is at the heart of the Rural Aperture Project, a new tool released by The Center on Rural Innovation (CORI). Wildly incompatible federal definitions of what constitutes rural affect the distribution of billions of dollars in funding each year and shape how businesses, banks, and foundations view rural places and make investment decisions. This effort demonstrates how rural America is measured and defined can’t be separated from conversations around critical issues like education, health, racial equity, and economic opportunity.

- The first principle of Aspen CSG’s Measure Up: Call To Action explains how conventional measures of development progress are often inappropriate in rural communities, especially in places that have been historically discriminated against or economically disadvantaged. Instead, systems-level actors should measure and evaluate local work through critical “asset changes” that embrace a place’s specific economic sectors and geographies, identify obstacles, and gauge whether supports and systems are in place to catalyze and sustain progress.

- Reenvisioning Rural America posits seven different types of rural communities based on a statistical analysis of 50 different measures of assets using a community capital framework and broken down by census tract. This tool may offer local and systems practitioners a finer-grain understanding of local and regional assets.

Measuring assets helps strengthen relationships within urban and rural regions

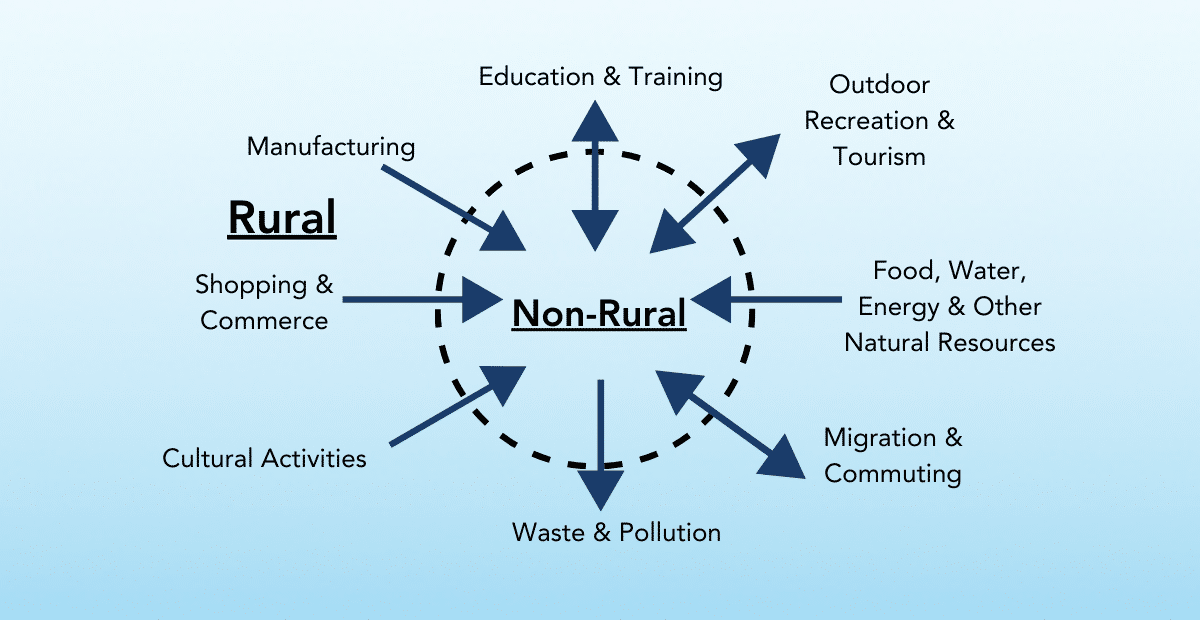

- Extraction and exploitation have been the norm in modern urban-rural relationships. But as Shanna Ratner explores in a recent segment of the Thrive Rural Field Perspective brief What (and Who) Counts?, evaluating local assets can provide an opportunity to “re-examine the ties between urban and rural with an eye toward turning existing systems that exploit rural for the benefit of urban into systems that are reciprocal and mutually beneficial.”

- Asset-based economic development techniques like WealthWorks help local people identify assets and develop those assets into value chains, growing local economies by connecting rural producers with urban commercial opportunities. Additionally, the Regional Solutions project findings suggest that value chains along with watersheds, commuting patterns, and rooted family connections offer opportunities to celebrate and leverage rural and urban interactions to repair strained regional relationships.

- A Thrive Rural Field Perspective brief on Native Nation Building offers multiple examples of the economic and political importance of rural Native nations within their wider regions. Native nations are economic engines and political centers, and “the benefits arising from tribal citizens’ financial and human capital gains are spread throughout the region.” When this is paired with the ecological and cultural benefits from the return of ancestral lands (as noted above), Native nations stand at the forefront of asset-based rural development.

Outstanding Questions for the Field

Asset-based development and asset-framing are key tools in the healthy development of Native nations and rural regions, but the learnings above raise new questions.

- What will it take for systems-level actors to incorporate new measures into their rural work? New measures for rural assets bump up against inequitable status quo power dynamics. One place of valuable future work will be to illuminate effective ways for systems-level actors to incorporate these new measures and how local and regional folks can hold them accountable.

- Where are the biggest opportunities or leverage points to reset rural-urban regional relationships? One valuable area of future work would be to elevate stories and lessons on rural regions that have equitably leveraged rural assets to strengthen their bargaining position vis-a-vis urban areas within a region. Major investments in clean energy infrastructure may provide a new opportunity to demonstrate and elevate the central importance of rural regions within global economic systems.

- What will it take for national narratives to consistently use rural asset framing? Asset frames can demonstrate that rural places are hotbeds of opportunity, but this narrative seems miles apart from most national media coverage of rural issues. One area of future work would be to promote rural realities within the national media and with media influencers by dispelling myths and increasing familiarity. This may also go a long way to helping reset the rural-urban relationship described above.

This reflection was written by Devin Deaton, Aspen CSG Action Learning Manager, and all Aspen CSG staff contributed to the insights and questions.

One of the goals of the Thrive Rural effort is to regularly synthesize insights we are learning through our engagements with the wider field of rural prosperity. This blog is the first in a new series that leans into and synthesizes broader field insights, using the framework as a lens. Not only can we pull together and show commonalities across seemingly disparate topics, but we can also illuminate gaps and areas to improve the Thrive Rural Framework.

We’d love to hear about what you are learning or learn directly from you. Contact us to share your ideas or resources.