View this Publication

Welcome — use the sidebar to navigate to different report sections. Get quick takeaways in the Executive Summary.

Introduction

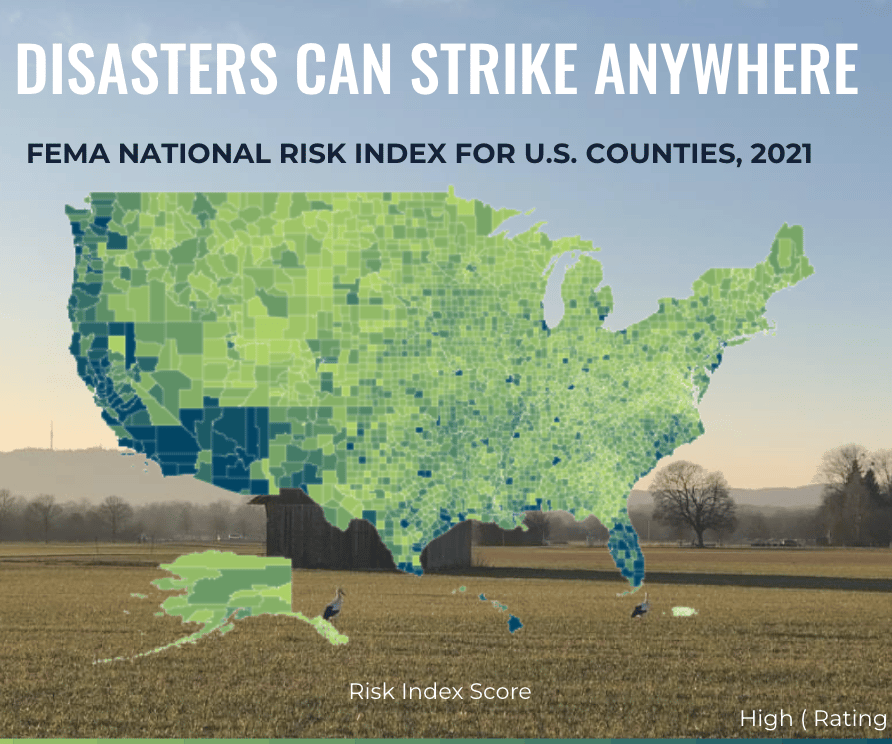

From fires to flooding, the geography and exposure to natural disasters in rural America are vast, but its capacity to prepare and respond to disasters is not.

As climate change continues to drive the increasing frequency and intensity of natural disasters, we have an opportunity to meet the moment by changing the way we approach rural disaster work and filling critical gaps in current efforts.

At the most fundamental level, this will require a reorientation of disaster work from a focus on just fixing what disasters break (an insurance or replacement approach) to a broader focus on advancing equitable community development outcomes (a community prosperity or opportunity approach). This shift in focus will enable disaster work to move out of a “patch it again” cycle and onto a trajectory that advances fundamental community prosperity outcomes, ultimately leading to healthy and thriving people in strong and stable rural communities and Native nations.

Too often, rural and Indigenous people, communities, and leaders are praised for their heroic “resilience” in the face of almost unimaginable damage and trauma when they gather their communities together and help each other with minimal outside resources and support. We assert that, while genuinely heroic and admirable, these efforts should not be necessary. As a nation, we should not expect already under-resourced communities to repeatedly pull themselves up by their proverbial bootstraps. At all levels, we need to ensure that rural communities and Native nations have the resources they need to prepare for, respond to, and recover from disasters in a way that advances community prosperity — and the prosperity of the United States as a whole.

The state and federal level needs a shift in approach—just because a community has been hit by a disaster does not mean that they’re incapable or don’t have any ideas around recovery.

Janice Ikeda, Vibrant Hawai’i

Additionally, for a host of reasons explored in this Call to Action, rural and Indigenous communities are more vulnerable to the impact of natural disasters and face different post-disaster recovery challenges than urban and suburban neighbors. The principles shared here are specific to rural and Native nation communities, but every effort, whether rural, urban or suburban, can become more effective by incorporating these principles.

CASE STUDY: The Aldrich Resilience Lab at Northeastern University recently published research highlighting the value of an equitable community prosperity approach. Studying Louisiana parishes impacted by Hurricanes Katrina and Rita in 2005, they found that communities using people-focused, community-driven “soft” policy tools recovered more effectively than those relying on outside, top-down approaches or “hard” infrastructure projects. Their recommendations stress that strong community leadership and voice — both before and after disasters — are essential for successful recovery.

Community Prosperity Approach: Focus on improving outcomes, not just maintaining or rebuilding the status quo

Traditional disaster response focuses on protection, repair, and preservation — protecting a community’s existing infrastructure and resources and, after a disaster, repairing them to maintain pre-disaster conditions. But given the inequities of place, race, and class affecting many rural communities, this “insurance approach” is inadequate. For instance, in a racially segregated and disinvested community, rebuilding may mean reconstructing substandard housing, rebuilding in flood-prone areas, and reproducing inequitable outcomes for health and prosperity. Other status quo responses, like demolishing unsafe housing without providing alternatives or restricting rebuilding in high-risk zones, often lead to further displacement of vulnerable households. Moreover, the insurance approach’s focus on individual property repair and compensation overlooks broader community dynamics, health, and prosperity.

The principles from the TRALE process instead center on an equitable community prosperity approach. This approach seeks not merely to preserve current conditions but to improve health and economic outcomes for rural communities. Grounded in the Thrive Rural Framework, it emphasizes holistic progress — enhancing the overall health of the community rather than simply repairing what is broken. It is also strengths-based, leveraging existing assets and engaging residents as active creators and shapers of their communities’ futures.

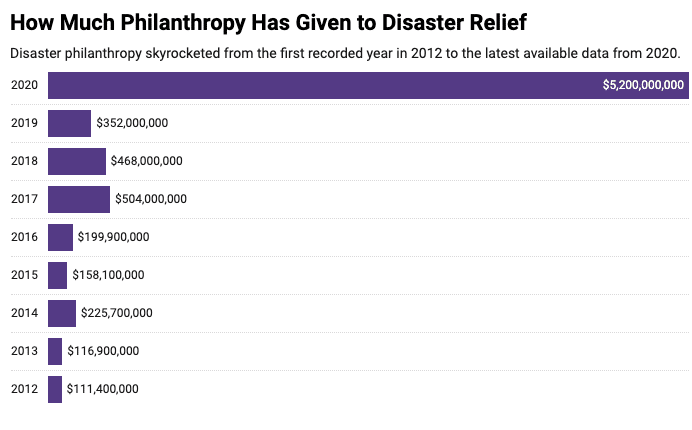

Beyond addressing equity and local impacts, the equitable community prosperity approach offers broader benefits by improving taxpayers’ return on investment for disaster spending, which continues to grow as a share of federal expenditures. Communities left weakened after disasters remain highly vulnerable, requiring repeated infusions of funding to recover. By contrast, communities that emerge stronger and more resilient after disasters can better withstand future shocks, creating a virtuous cycle that supports not only local prosperity but also long-term national prosperity.

This Call to Action aims to equip systems-level actors (from federal disaster response agencies to national non-profits) with equity-centered principles that, if adopted, will improve their work with rural and Native nation communities. And because this document centers the ideas of rural thinkers and doers, it gives local leaders a tool to inspire equitable action at the local level. Intentional, collaborative action at both the local and systems levels will work to grow equitable rural prosperity and dismantle systemic discrimination based on race, geography, and economic status within the field of rural disaster planning and response.

DEFINITIONS

The definitions below are terms and concepts used regularly in this Call to Action. These definitions should not be considered exhaustive or final but act as a baseline for readers to understand the context and issues discussed in this document.

Disaster refers to an event such as a storm, fire, or flood that causes severe damage or death within a community or geographic area. We also acknowledge that rural communities and Native nations experience “slow-moving disasters” related to our changing climate, systemic inequity, and/or disinvestment.

Disaster mitigation refers to efforts to reduce the risk of damage from future disasters.

Planning refers to creating and adopting concrete plans for community development (e.g., economic development, built environment) and/or disaster mitigation.

Disaster preparedness includes planning, mitigation, and other efforts to strengthen a community and its infrastructure to better respond to and recover from a future disaster.

Disaster response refers to meeting immediate human and infrastructure needs following a disaster. Disaster recovery refers to mid-term efforts to address the damage caused by a disaster.

Resilience refers to the long-term ability of built infrastructure to withstand disasters. We do not use this term to refer to communities or people, given that rural and Indigenous people and communities have too often been praised for being resilient — at the expense of a real effort to create equitable conditions on the ground.

TRALE Process: Structure and Participants

This Call to Action is the result of a Thrive Rural Action-Learning Exchange (TRALE). TRALE is a process that quickly taps on-the-ground insights and experiences to help generate breakthrough thinking about what works and what’s needed to push rural policy and practice forward. The Aspen Institute Community Strategies Group (Aspen CSG) conducts each TRALE process, working with various collaborating partners to ensure a strong representation of rural communities and Native nations.

For this TRALE process, Aspen CSG convened 39 seasoned rural economic and community development practitioners from rural communities and Native nations across the United States. These rural practitioners, advocates, and innovators shared their experiences and ideas to answer the question, “What will it take for rural and Native nations communities to make progress towards long-term resilience from natural disasters?”. Collectively, the diverse participants account for hundreds of years of experience in rural economic development, community human services and health, housing, transportation, small business development, family asset building, development finance, grassroots community engagement and advocacy, and regional development. They are respected, committed leaders in their communities, representing all regions of the United States, from the Pacific Islands to the Southeast.

Is it the same old, same old people that are going to get these resources, or can this be an opportunity for transformation? And how does community voice get into this?

Karen Minyard, Georgia Health Policy Center

Principle 1: Understand and address the underlying conditions affecting rural disaster vulnerability, response, and recovery.

Disasters happen in places, and specific conditions shape each place. The natural, physical, social, and policy landscapes of rural communities and Native nations affect the communities’ vulnerability to disasters and their ability to respond to and recover from them.

Disaster response and preparedness programs that fail to account for long-term local and systems conditions are less likely to succeed. They can even do harm or perpetuate patterns of inequity and distrust (see Principle 3).

Long-term disinvestment, crumbling or absent infrastructure, and lack of institutional capacity (due to inadequate funding support) are part of the landscape in many rural communities and Native nations (see Principle 4). And for many rural communities of color and Native nations, these inequities are compounded by structural discrimination and traumatic histories of colonization, genocide, slavery, and racial violence. These conditions make many rural communities especially vulnerable to the impacts of natural disasters — and make it more challenging to recover and thrive. And in many cases, challenging local conditions may add up to a “slow-moving disaster” as impacts build over time (e.g., from environmental degradation or climate change).

Housing, for example, has been an infrastructure challenge for many years. A rural community with deteriorating housing stock located primarily in a flood plain will see a disproportionate disaster impact and will have a much longer and more difficult road to recovery than a community with good quality, safely-sited housing. And as our changing climate intensifies the magnitude and frequency of disasters such as storms, fires, and floods, rural communities and Native nations will be especially vulnerable.

Overall population health is another critical underlying condition that affects disaster vulnerability and impact. Communities with high rates of chronic health conditions will have different needs in the immediate aftermath of a disaster, and the stress of a disaster may exacerbate existing conditions, worsening health outcomes.

“It’s not just that a hurricane occurs — there isn’t the underlying infrastructure to begin with. When it rains, we experience constant flooding not only because of the natural disaster, but because the community never had the infrastructure to handle even a little rain, let alone the massive rainfall of a hurricane. We assume that communities can bounce back and be resilient, but in reality, many homes were already in fragile, detrimental conditions before the disaster. In these cases, the idea of rebuilding or repairing is nonexistent because there was never a strong foundation to rebuild from. Instead, recovery often becomes a process of tearing down and starting over.”

Zoraima Diaz, Come Dream Come Build

“There is often an inventory of plans in a community — infrastructure, housing, and land use plans — but it is critical that these plans are not in conflict. For example, a mitigation plan may call for building outside the floodplain, while an economic development plan calls for a riverfront entertainment district, creating incompatible priorities. Local plans should be reviewed to ensure they are complementary and not unintentionally exacerbating problems.”

John Cooper Jr., Texas A&M

While some local conditions can make rural communities and Native nations more vulnerable to the impacts of disasters, other conditions can strengthen these communities’ ability to prepare and respond. For example, these communities may have strong social ties and informal networks that can be activated during a crisis to respond quickly and save lives. Community elders, leaders, and organizers understand where the physical and social resources are in a rural area and how to engage them effectively. Elders may also have valuable insight into reciprocal relationships between people and the land (see Principle 2). Given the diversity of conditions on the ground and the fact that rural people know their communities best, disaster-response and resilience-building programs must partner with local people to learn, respond, and build trust before, during, and after a disaster.

To build thriving communities that can respond to and recover from acute disasters, we need to move away from the insurance approach to disaster response to a community prosperity approach that builds on each community’s unique conditions, including strengths and challenges

“One piece I feel is missing from a lot of work with communities is the connection to the aunties and the grandmas, whoever those folks are in a particular community — the unofficial leaders who will stick with the people through recovery and as they prepare for the next disaster.”

Samantha Estabrook, Headwaters Economics

CASE STUDY: FLOODING IN CENTRAL APPALACHIA

The Summer 2022 flash flooding in Central Appalachia (in Eastern Kentucky and Southern West Virginia) is an instructive example of how local conditions can intensify the impact of a natural disaster. Long a site of fossil fuel extraction, the region has seen an intensification of damaging surface coal mining, including large-scale mountaintop removal mining in recent generations. Local economies have risen and fallen with the coal industry, and even as well-paying coal jobs dwindle with automation, local community identities are often tied to coal.

This leaves Central Appalachian communities trapped in a vicious cycle: coal-burning power plants release large amounts of carbon, driving climate change; climate change increases the frequency and intensity of heavy rain events, especially in this region; and land that has been subject to surface mining sees dramatic increases in runoff, as the damaged land can’t absorb the water. Within this cycle, communities affected by a decline in coal jobs are in an economic position that makes it difficult to prepare for, respond to, and recover from disasters. This is in addition to the negative human health consequences of both coal mining (e.g., black lung disease) and economic disinvestment.

Strong social ties have helped people in Central Appalachia recover from many disasters, and we can already see community commitment at work in this case. And while the people of this region are often praised for being self-reliant and scrappy, we contend that as a nation, we should not be asking them to interrupt this vicious cycle on their own. With a community prosperity approach and adequate resources to implement it, the strong leadership and energy in Central Appalachian communities could be directed toward building thriving, healthy communities and economies with truly resilient infrastructure — improving outcomes for everyone.

Recommendations

Government

- Promote or expand policies and programs that conserve or restore natural ecosystems and working landscapes.

- Support basic research that grows our understanding of reciprocity between humans and natural systems and that includes representation from a wide spectrum of expertise, including Indigenous perspectives.

- Increase staff literacy regarding Native nations’ history and concerns, both to facilitate respectful and effective working relationships and to integrate Indigenous perspectives into broader work.

- Support practical collaboration within and across regions to advance learning and integrate consideration of reciprocity between human and natural systems into community development work.

Philanthropy

- Convene peer learning networks to facilitate a deeper understanding of reciprocity between humans and natural systems, and that includes representation from a wide spectrum of expertise (e.g., faith communities, science, and Indigenous perspectives).

- Support work within Native nations to explore and document place-based knowledge and approaches to community prosperity and disasters.

- Increase staff and grantee literacy regarding Indigenous history and expertise to facilitate respectful and effective working relationships and integrate Indigenous perspectives into broader work.

- Document effectiveness of regenerative strategies and approaches to community prosperity and disaster mitigation.

- Lift up and disseminate stories of a healthy balance between humans and natural systems and the relationship of this balance to rural communities and Native nations’ vulnerability to, response to, and recovery from disasters.

Rural Practitioners

- Integrate consideration of balance and reciprocity between human and natural systems into community prosperity and disaster work.

- Intentionally design efforts to engage diverse perspectives, including Native nation communities, to learn how to better incorporate regenerative practices and approaches within inclusive local and regional efforts.

Principle 2: Advance worldviews that restore balance and relationships among communities and natural systems.

During TRALE conversations, the need to shift how we relate to the natural world emerged as a strong theme. Extractive and exploitative relationships with natural systems produce conditions that promote natural disasters — and make it difficult to prepare for and respond to them.

While human-driven climate change, which is increasing the frequency and intensity of natural disasters, is an example of this type of unsustainable and exploitative relationship on a grand scale, the principle applies at all levels and scales — from the siting and design of homes and roadways to the preservation or destruction of protective ecological systems like wetlands.

To create the conditions (see Principle 1) for thriving rural communities and Native nations with resilient infrastructure, we need to shift our worldviews to accommodate a full and balanced picture of the reciprocal relationships between human beings and the natural world. (For example, see the Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services’ recent paper, Valuing nature’s contributions to people.) A full understanding of the truly interconnected nature of human and ecological health could lead to breakthroughs that advance health outcomes and health equity. Such a worldview shift would significantly impact disaster preparedness, response, and recovery, allowing rural communities and Native nations to move beyond the “insurance approach” (see Introduction) and address the roots of disaster, setting the stage for truly thriving social and ecological communities.

TRALE participants noted that Indigenous people’s knowledge of and connections to natural systems and place provide a grounded, real-world example of reciprocity between the human and natural worlds. (For more on the importance of reciprocity, see the work of Robin Wall Kimmerer, including The Serviceberry.) In TRALE discussions, we heard voices from Native nations that are succeeding at reestablishing a balanced life in the face of hundreds of years of oppression — disaster on a monumental scale. Rural communities across the country have much to learn from Indigenous communities undertaking this work. Still, that learning itself must be balanced and reciprocal, not extractive or exploitative — undertaken with humility on the part of the learners and just compensation for those sharing experiences and knowledge.

“I think it’s really important to listen to the people who have lived on the land the longest, to hear their communities and value the knowledge they hold about what works and what doesn’t. More importantly, we must be respectful of Mother Nature and stop planning practices that put people in harm’s way. In California, for example, building new communities in the foothills of the Sierras — where the forest naturally regenerates through fire — ensures that residents will eventually face fire. Similarly, placing homes on land that was swamp just 25 years ago almost guarantees flooding. Continuing these practices is irresponsible and only sets us up for failure.”

Sharon Reilly, Great Lakes Inter-Tribal Council

“Two hurricanes left the Upper Coharie River in North Carolina completely clogged with debris. In response, the Coharie, a state-recognized tribe, engaged young tribal members in stream restoration, teaching them to clear logs and obstructions from a small section of the river. When Hurricane Matthew struck that year, roads remained underwater for nearly two weeks. Two years later, after the tribe had restored almost 30 miles of river, Hurricane Florence brought far more severe flooding — yet the roads were clear within two days. This success led the tribe to create an LLC that now generates revenue, creates jobs, and provides environmental clean-up and stream restoration training in two states.”

Mikki Sager, Self-Employed

““There is often a lack of consent with regard to the needs of Indigenous communities. The people closest to challenges have valuable insight into solutions, and unfortunately, scholars and people outside of our communities often think that they know more about the science behind the changes that are occurring in the community. Well, the people of the community have long-standing intelligence about and knowledge about how things have changed over time. For example, how snow has changed and how the seasons have changed, getting longer or shorter depending upon various elements and cycles. Especially with climate change, we are seeing them becoming shorter and shorter. So what needs to happen first of all is acknowledging the sovereignty of Indigenous communities and then second to recognize that they have thousands of years of expertise.”

Sophia Marjanovic, Union of Concerned Scientists

Recommendations

Government

- Promote or expand policies and programs that conserve or restore natural ecosystems and working landscapes.

- Support basic research that grows our understanding of reciprocity between humans and natural systems and that includes representation from a wide spectrum of expertise, including Indigenous perspectives.

- Increase staff literacy regarding Native nations’ history and concerns, both to facilitate respectful and effective working relationships and to integrate Indigenous perspectives into broader work.

- Support practical collaboration within and across regions to advance learning and integrate consideration of reciprocity between human and natural systems into community development work.

Philanthropy

- Convene peer learning networks to facilitate a deeper understanding of reciprocity between humans and natural systems, and that includes representation from a wide spectrum of expertise (e.g., faith communities, science, and Indigenous perspectives).

- Support work within Native nations to explore and document place-based knowledge and approaches to community prosperity and disasters.

- Increase staff and grantee literacy regarding Indigenous history and expertise to facilitate respectful and effective working relationships and integrate Indigenous perspectives into broader work.

- Document effectiveness of regenerative strategies and approaches to community prosperity and disaster mitigation.

- Lift up and disseminate stories of a healthy balance between humans and natural systems and the relationship of this balance to rural communities and Native nations’ vulnerability to, response to, and recovery from disasters.

Rural Practitioners

- Integrate consideration of balance and reciprocity between human and natural systems into community prosperity and disaster work.

- Intentionally design efforts to engage diverse perspectives, including Native nation communities, to learn how to better incorporate regenerative practices and approaches within inclusive local and regional efforts.

Principle 3: Use disaster response to advance equity and increase regional prosperity.

As we saw in the discussion of rural conditions (see Principle 1), historic inequities exacerbate disaster impacts. Communities with more poverty and less capacity due to structural discrimination and disinvestment may be more vulnerable to the impacts of natural disasters and less able to access and activate the resources necessary for recovery and long-term prosperity.

“When we go in to do recovery in these communities, what does equity look like? What does recovery look like when a community has this background, this history as its foundation?”

Simonne Dunn, FEMA

If disaster preparedness, response, and recovery programs are not intentionally designed to mitigate and address inequities, including interventions to propel communities to more prosperous futures, they risk perpetuating inequality or making these regions less prosperous.

For example, suppose recovery assistance is complex or difficult to access (e.g., applicants need a computer to submit forms, instructions are not available in the language community members are most comfortable using, or assistance is only available during limited business hours). In that case, the most privileged members of the community — those with the most time, connections, and resources — will be more likely to receive recovery assistance than those who most need it, deepening and reinforcing inequities within the community. The same principle applies across regions: the more complex or challenging assistance is to access, the more likely that places with fewer resources will receive less assistance, widening gaps between communities.

“The big problem with a lot of very small communities is they might have access to funds, but every big city is also eligible, including Houston, Austin, and San Antonio. The little communities don’t get enough resources to recover.”

Harold Hunter, Communities Unlimited

Inequitable disaster response and a lack of equitable disaster recovery have a compounding impact on social determinants of health and health outcomes over repeated disaster cycles and, ultimately, generations. Conversely, improving equity in disaster response has the potential to improve the social determinants of health — and, thereby, health outcomes — for communities that have experienced some of the deepest health challenges in the nation.

“It’s important that government leaders have humility and accept and acknowledge that we don’t have all the answers. In the end, it’s really the people who are impacted directly or helping to lift themselves up as well as lift one another up. Government cannot be seen as the normal be-all resource to fix every problem a community faces, but rather government should be there to support the community developing its own strategies.”

Darryl Oliveira, HPM Hawaii

One important way to design disaster-related programs to advance equity is to ensure that those most affected are part of the leadership in planning, response, and recovery. The local community — especially those most affected by inequity and discrimination — needs to wield real power and exercise authentic leadership, especially in contexts where trust is absent because of past experiences of oppression or abuse from systems and institutions. And on a practical level, local grassroots leadership is often more likely to be effective than outside organizations (see asset discussion in Principle 1).

“The strongest solutions are very often practice-based. They are built by people who have intimate experiential knowledge of the geography, the culture,and the history.”

Gillian Mittelstaedt, Tribal Healthy Homes Network

Recommendations

Government

- Increase USDA Rural Development (RD) involvement in federal disaster management, leveraging RD’s deep knowledge of rural communities in groups such as the FEMA-led multi-agency taskforce.

- Build relationships in communities ahead of disasters, including with historically marginalized groups within communities.

- Facilitate inclusive planning processes, providing accessible spaces for all community members, regardless of needs (e.g., translation services, physically accessible spaces).

- Support local networks’ and organizations’ disaster planning, response, and recovery efforts, including by assessing and filling gaps in programming and funding opportunities that prevent certain types of organizations (e.g., community-based organizations, non-federally-recognized tribes) from engaging in this work.

- Prioritize local hiring and contracting for disaster work, given that community residents know the issues best and are best positioned to hit the ground running in a disaster situation.

Philanthropy

- Support research on and evaluation of equity and access in disaster preparation, response, and recovery (e.g., inclusion of grassroots non-profits in the work of state Emergency Operations Centers).

- Create regional relationships and networks to facilitate equitable disaster preparation, response, and recovery efforts.

- Engage with grassroots community groups early and often to support disaster preparation and to “pre-certify” organizations for rapid funding in the event of a disaster.

Rural Practitioners

- Bring people from across the community into disaster work. Ask who is missing from groups and collaborations, and engage them; this includes making spaces and systems accessible.

- Focus on improving outcomes for the community, especially for community members affected by structural discrimination. Shift disaster work from an insurance approach to an inclusive community prosperity approach.

“We have to look at the systems in terms of everybody’s needs, but also recognize that for a community of color within a rural region, the impact on that smaller population is amplified. It’s exponential compared to their urban counterparts because of isolation. So there has to be attention to the folks who are most in need, but we can’t just look at one group, we have to be applying it broadly, and our mainstream government and non-profit systems are just not set up to do that right now. We’re going to have to do disaster recovery differently.”

Calvin Allen, MDC Rural Forward

“Somebody brought up that the immediate response comes from neighbors, and that’s exactly what happened when we built this system, you know, out of nowhere. And so all of us began thinking, you know what this means — we can do this. We can do economic development in our communities, we can provide services in our communities, we can get water lines, we can do the infrastructure, we can do all this work. We have everything that it takes, we have the people that care, it’s just there’s another layer of this colonial power that still impacts our communities.”

Jessica Stago, Change Labs

“When I was with the Greater New Orleans Foundation, we pre-certified organizations to receive disaster response money. The pre-certification process includes getting all the needed documents for a grant in advance — 501(c)3 status, a short description of how the organization deploys resources after a disaster, bank information for ACH, etc. It speeds up the grantmaking process so that funds can be disbursed as soon as possible — giving non-profits the resources they need to immediately start their work helping communities affected by the disaster.”

Bonita Robertson-Hardy, Aspen CSG

“You hear a lot about procedural equity and planning and making sure that the process is inclusive and grounded in the local context. In low-resource communities, the lack of access to accurate, up-to-date data hampers the planning work. Data has to be accurate and grounded in the local context in order for the planning to be meaningful.”

John Cooper Jr., Texas A&M

“The strength is local formal and informal community leaders being involved and taking ownership in recovery.”

Heidi Schultz, Center for Disaster Philanthropy

“Recovery funding that goes to the big intermediaries should require or prioritize hiring local people and nonprofits that get paid to do the recovery work. We’ve seen, time and time again, recovery money going to one outside group, they hire people who are not from the community and then they ask local people and organizations to help them for free. Requiring or prioritizing hiring local people and groups would build on rural communities’ biggest assets: their people. It would help people who need the money and who know and are trusted by the community; and would get recovery resources to community members who would not otherwise be reached.”

Mikki Sager, Self-Empolyed

Principle 4: Build local and regional capacity to address disasters.

During TRALE conversations, the need to shift how we relate to the natural world emerged as a strong theme. Extractive and exploitative relationships with natural systems produce conditions that promote natural disasters — and make it difficult to prepare for and respond to them.

While human-driven climate change, which is increasing the frequency and intensity of natural disasters, is an example of this type of unsustainable and exploitative relationship on a grand scale, the principle applies at all levels and scales — from the siting and design of homes and roadways to the preservation or destruction of protective ecological systems like wetlands.

To create the conditions (see Principle 1) for thriving rural communities and Native nations with resilient infrastructure, we need to shift our worldviews to accommodate a full and balanced picture of the reciprocal relationships between human beings and the natural world. (For example, see the Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services’ recent paper, Valuing nature’s contributions to people.) A full understanding of the truly interconnected nature of human and ecological health could lead to breakthroughs that advance health outcomes and health equity. Such a worldview shift would significantly impact disaster preparedness, response, and recovery, allowing rural communities and Native nations to move beyond the “insurance approach” (see Introduction) and address the roots of disaster, setting the stage for truly thriving social and ecological communities.

CASE STUDY: Firewise Communities are multi-jurisdictional community-based responses to the risk of wildfire. Through the program, led by the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA), locally-led groups identify their community’s greatest risks for wildfire and different ways to respond to it. There are nearly 2,000 Firewise Communities across the United States. Communities of at least eight dwellings are recognized as “Firewise” after they complete these five steps:

1) Create a board or committee of residents and other local stakeholders interested in wildfire protection

2) Obtain a written wildfire risk assessment from the state forestry agency or local fire department that identifies risky areas and recommendations for improvement

3) Create an action plan to be updated every three years that identifies community education and mitigation activities

4) Host an outreach and education event that addresses items from the action plan

5) Track the hours and financial investments from the community in wildfire mitigation

“In 2017, we started the work around building community leadership teams — diverse leadership teams that reflect the demographics in the community. This is challenging to do in the South, but it’s important because if you don’t have all the voices at the table, then the decisions just keep repeating themselves, historically. What we found was that the communities that had leadership teams had a way to respond to COVID that other communities did not have. Very quickly, the folks who were used to working together mobilized themselves to do outreach to small businesses and figured out how to keep them afloat. Once you build the infrastructure of that team, it sort of mobilizes itself. Can you imagine what that would look like in a climate disaster environment, where you’re not coming in after the disaster to organize the team, but the team is already there?”

Ines Polonius, Communities Unlimited

“Practitioners have the trust of community members because they’re part of the community, and that’s critical. But if the practitioners themselves don’t have the capacity or ability to understand the regulatory policy as it’s coming down, then there is a lot of stress on the practitioner that they’re not imparting the correct knowledge to the community. It is stressful for local communities that don’t have the capacity to understand the regulation in real-time. It causes fear about what to do, and that’s exactly what you don’t want to get at the end of the day — misappropriate funds.”

Zoraima Diaz, Come Dream Come Build

“There are just so many hoops to jump through for programs that look really great on paper, but in actuality, resources never get to the places where they’re most needed.”

Karen Affeld, North Olympic Peninsula Resource Conservation & Development Council

“These communities don’t have the infrastructure, they do not have the staff, they do not have the professional human resources to develop plans for their communities, towns, and villages; it’s not there. Many of them do not even understand that they need to have a plan for sustainability. Intermediaries need to step up their game; they need to reimagine how they are going to relate to our communities, and funders need to stop looking at these mega communities and thinking that because our organizations are small, we do not have the capacity to do the work in the communities that we do. Because we’re going to be here when the intermediaries and all the rest of them have come and gone, whether there is funding on the table, or whether there is not; we’re going to be here because this is where we live.”

Romona Taylor Williams, MS Communities United for Prosperity

“Seems like every time something happens, we have to make it all up again. When the feds are involved, they’re in charge, and then they come and go, and then the state comes and goes. Eventually, it’s going to be the local people that are left dealing with the situation, and there’s no continuity of command and control — there’s no real long-term cooperation. Everything happens in phases, and different people are in charge in different phases, and that makes it really hard to coordinate a long-term response.”

Michael Howard, ARCH Community Health Coalition

Recommendations

Government

- Establish inclusive cross-sector local leadership teams to plan for, respond to, and support recovery from disasters and provide consistent agency participation and support over time.

- Incentivize agency participation in and prioritization of community-led efforts.

- Engage connected institutions on leadership teams (e.g., Economic Development Administration–funded regional councils of government, Land-Grant affiliated Extension Service offices).

- Train agency staff on working with rural communities and Native nations.

- Provide training and materials to local leadership teams and organizations, including on disaster planning, response simulations, and mitigation efforts.

- Designate local “navigators” to help communities negotiate complex federal disaster systems, including funding and planning assistance.

- Streamline complex systems and requirements to allow communities to focus on the work at hand.

- Align evaluation systems across agencies and sectors to avoid duplicative and onerous data collection and allow communities to focus on the work.

Philanthropy

- Support development of local leadership teams as they build infrastructure for disaster planning, response, and recovery.

- Develop and pilot programs that help communities navigate complex federal systems. While public navigator systems are ideal, philanthropy can support this development by funding projects that test and pilot these ideas.

- Help develop and pilot local information-sharing systems. Publish learnings so communities can build their own systems.

- Provide fiscal agency support to smaller community organizations that are not able to take on the risk and burden of federal funding.

- Provide technical assistance with federal systems, including funding grant development and administration support as necessary.

- Launch the development of continuity of operations plans for local and regional non-profits. Hold workshops or create workbooks with model plans that can help practitioners prepare their organization to be in working order during and after a disaster.

- Align reporting and evaluation systems across funders and sectors to avoid duplicative and onerous data collection and allow communities to focus on the work.

- Align internal evaluation and measurement with intended outcomes, including measuring inclusion and equity outcomes.

Rural Practitioners

- Create “care infrastructure” for the community, including local cross-sector leadership teams.

- Create disaster plans for community-based organizations, including detailed continuity of operations plans that explain what to do to keep the organization in action to support the community in the event of a disaster.

- Gather information on local, regional, and national resources before a disaster strikes; know who is in charge of what resources and how they can be accessed.

“If FEMA is embedded in the places where these disasters tend to occur, then it may make the response and the planning efforts a bit more effective and efficient.”

Alison Davis, Community and Economic Development Initiative of Kentucky, University of Kentucky

“Getting people involved in the information gathering and dissemination process helps them build confidence and understanding of what’s happening and why, and then what they can actually do to address it or to hold people accountable.”

Lyndsey Gilpin, Southerly Magazine

“You can say a lot of nice words as a local leader of an agency that you care about community input, but at the end of the day, you’re not measured on those data, and budgets aren’t allocated on those things, so I think until we start to shift that bureaucratic architecture we’re always pushing a rock uphill.”

Tyson Bertone-Riggs, Rural Voices for Conservation Coalition

“We typically talk about building capacity for community leaders. There’s also a need to build the capacity of state and local government officials so they can better engage community equitably.”

Andrew Shoenig, MDC Rural Forward

Principle 5: Provide flexible and responsive funding for disaster preparation, response, and recovery.

A strong theme throughout the TRALE conversations was the high level of complexity, even rigidity, involved with disaster funding, especially at the federal level.

Many participants expressed frustration at the limitations of the funding available, which is designed from the more narrow perspective of an insurance approach, rather than a community prosperity approach to disasters (see Introduction). Additional complexity comes from the need to stitch together multiple funding sources, which may have conflicting requirements. For example, accepting one set of funds can cut a community off from more significant funding in the future.

Beyond the challenges of limitations and strictures on funding, many participants expressed fear around engaging with federal funding, given the high stakes involved with potentially making a mistake, even a small error, in project administration or reporting. Making a mistake on complex federal grant administration and therefore having to return funds could mean the end of a small community organization — or even jail time for staff!

Flexible, responsive funding opportunities could enable rural communities and Native nations to take a community prosperity approach to disaster preparedness, response, and recovery, improving outcomes and building long-term prosperity for all. This could mean streamlining processes and creating new, flexible programs at the federal and state levels. For philanthropic funders, it could mean proactive outreach and pre-certification, as well as developing programs to fill gaps and pilot new approaches.

“How do we create a structure where folks can access resources that’s not as complicated as some of these federal grants?”

Ines Polonius, Communities Unlimited

“In many cases, if you take funds from another agency to address some of these recovery needs, it can eliminate your ability to actually draw down FEMA funds. That would be one really quick, and maybe easy, piece for the Federal family to think about. Why are we preventing communities from taking funds that can address things quickly?”

Nathan Ohle, International Economic Development Council

“There is this huge push for no mistakes in administering these funds. It’s unreasonable — humans make mistakes. Nobody does things perfectly all the time, and when you have millions of dollars of awards, people are going to make mistakes — what’s the expectation of a reasonable mistake? I would love to see the work of someone who’s actually analyzed this.”

Jessica Whitehead, Institute for Coastal Adaptation and Resilience, Old Dominion University

“It is critical to be responsive during emergency situations and to be flexible with funding. We (The Ford Family Foundation) reached out to communities in need and provided them the resources they needed. We eliminated barriers and requirements — final reports as an example. We learned that in crisis situation it is critical that philanthropy be responsive to the needs of the people they serve and respect the realities of their experience.”

Roque Barros, Imperial Valley Wellness Foundation

Recommendations

Government

- Change regulations that can prevent communities from accessing FEMA funds if they accept funding from other sources. Communities need both immediate and long-term assistance, and FEMA regulations should reflect this reality.

- Develop short-term “bridge funding” for communities. This could involve zero-interest loans for businesses until FEMA funds begin to flow.

- Create programs that fund long-term prosperity and sustainability, not just immediate disaster needs.

- Create funding programs flexible enough to meet specific local needs. Not all communities need to do the same things to prepare for, respond to, or recover from a disaster. Funding programs should allow communities to make a case for their resilience needs rather than dictating approaches.

- Clarify and simplify regulations related to managing disaster funding to increase access for smaller organizations and communities. This is particularly important for Native nations that rely on direct aid from the federal government and where jurisdictions are fuzzy between states and tribes.

- Trust rural people and communities to make responsive, quick, and wise decisions about spending money in a disasters

Philanthropy

- Support accountability analysis of public and private disaster funding to assess impact on equity and community prosperity outcomes.

- Create low-friction systems to distribute funding after a disaster, including pre-certifying organizations and simplifying administration and reporting requirements.

- Provide short-term “bridge funding” for communities to fill gaps before federal funds begin to flow.

Rural Practitioners

- Assess potential needs and develop possible spending plans for flexible disaster funding.

“The town was in disaster response mode, trying to do the best that they could, and the mayor ended up getting indicted for misuse of federal funds — sentenced to prison for his misuse of about $1,000. It created a lot of fear in local city officials about using federal funds. There’s not the state capacity to come in and support a town of 2000 people to help them manage hundreds of millions of dollars of federal funds, so how do we address that fear that people now have, and also help them have the capacity to manage those resources when they come in?”

Stephanie Tyree, West Virginia Community Development Hub

“Our tribe, the Navajo Nation, like all tribes across the United States, has a special political relationship with the federal government. And that relationship requires that the federal government provide certain funding directly to tribes. And so there’s always that boundary — when there’s a disaster, do we consider that part of the state of Arizona? Do we consider it Navajo Nation? And if it’s the Navajo Nation, then our funding has to go through the federal government to the Navajo Nation. Our tribes have these colonial systems that were put in place that really restrict the flow of funding down into our communities.”

Jessica Stago, Change Labs/Grand Canyon Trust Arizona

“It was interesting to learn how funders thought about us and our capacity. I think that’s a big piece of this when we talk about getting funding to minority leaders and to small organizations. One woman called me and was going to give us a grant. She said, ‘Do you know anyone in Chicago or the Twin Cities who could be the fiscal agent?’ And I was like, we absolutely have the capacity to be the fiscal agent for this!”

Nancy Van Milligen, Community Foundation of Greater Dubuque

“I think there is a big role for philanthropy to not only invest in more capacity for communities through programs but also help provide accountability for federal funds from FEMA.”

Astrid Caldas, Union of Concerned Scientists

Participant List

Charlie Alfaro, Executive Advisor, Center for Health Innovation, New Mexico; Karen Affeld, Executive Director, North Olympic Peninsula Resource Conservation & Development Council, Washington; Calvin Allen, Senior Director, MDC Rural Forward, North Carolina; Roque Barros, Executive Director, Imperial Valley Wellness Foundation, California; Tyson Bertone-Riggs, Former Coalition Director, Rural Voices for Conservation Coalition, Oregon; Astrid Caldas, Senior Climate Scientist for Community Resilience, Union of Concerned Scientists, Maryland; Kyril Calsoyas, Navajo Trust Foundation, Arizona; Nils Christoffersen, Executive Director, Wallowa Resources, Oregon; John T. Cooper Jr., Assistant Vice President for Public Partnership & Outreach, Texas A&M University, Texas; Cari Cullen, Director of the Midwest Early Recovery Fund, Center for Disaster Philanthropy, North Dakota/Minnesota; Alison Davis, H.B. Price Professor, Department of Agricultural Economics, Executive Director, Community and Economic Development Initiative of Kentucky, University of Kentucky, Kentucky; Zoraima Diaz-Pineda, Director of Policy, Come Dream Come Build, Texas; Simonne Dunn, Recovery Planning Coordinator, FEMA, Georgia; Samantha Estabrook, Planner, Headwaters Economics, Kansas; Lyndsey Gilpin, Founder and Editor-in-Chief, Southerly Magazine, Kentucky; Mark Haggerty, Senior Fellow – Energy and Environment, Center for American Progress, Montana; Megan Hess, Rural Organizing Director, We the People Michigan, Michigan; Michael Howard, CEO, ARCH Community Health Coalition, Kentucky; Harold Hunter, Texas State Lead, Communities Unlimited, Texas; Janice Ikeda, Executive Director, Vibrant Hawai’i, Hawaii; Ka’ae Lyons, HPM Hawaii, Hawaii; Sophia Marjanovic, Bilingual Senior Organizer, Union of Concerned Scientists, Maryland; Karen Minyard, CEO, Georgia Health Policy Center, Georgia; Gillian Mittelstaedt, President, Tribal Healthy Homes Network, Washington; John Molinaro, Principal, RES Associates LLC, Ohio; Nathan Ohle, President and CEO, International Economic Development Council, Washington DC; Darryl Oliveira, HPM Safety and Internal Control Manager, HPM Hawaii, Hawaii; Susie Osbourne, Head of School, Kua O Ka Lā PCS, Hawaii; Nola Osinubi, Former Research Fellow, Center on Rural Innovation, Georgia; Andrea Osorio, Former Program Associate for Economic Mobility & Disaster Response, Cognizant, and Former Disaster Response Team Member, GlobalGiving, Washington DC; Ines Polonius, CEO, Communities Unlimited, Arkansas; Sharon Reilly, Planning and Development Director, Great Lakes Inter-Tribal Council, Wisconsin; Mikki Sager, Self-Employed, Former Vice President of the Conservation Fund, North Carolina; Heidi Schultz, Program Manager, Tribal and Native Communities Disaster Recovery Program, Center for Disaster Philanthropy, South Dakota; Andrew Shoenig, Program Director for Community Resilience, MDC Rural Forward, North Carolina; Jessica Stago, Director of Economic Initiatives, Change Labs/Grand Canyon Trust, Arizona; Romona Taylor Williams, Executive Director, MS Communities United for Prosperity (MCUP), Mississippi; Stephanie Tyree, Executive Director, West Virginia Community Development Hub, West Virginia; Nancy Van Milligen, President and CEO, Community Foundation of Greater Dubuque, Iowa; Jessica Whitehead, Joan P. Brock Endowed Executive Director, Institute for Coastal Adaptation and Resilience, Old Dominion University, Virginia.

The following people worked together to shape this Call to Action:

- Action-Learning Exchanges were facilitated by Chris Estes, with coordination support from Tyler Bowders.

- Aspen CSG’s consultant Jason Gray assisted in the interview process, identified the themes, and highlighted participant quotes and stories.

- Aspen CSG’s consultant Rebecca Huenink led the writing process.

- The entire Aspen CSG staff – Bonita Robertson-Hardy, Chris Estes, Erin Cahill, Devin Deaton, and Tyler Bowders – helped edit and sharpen the concepts.