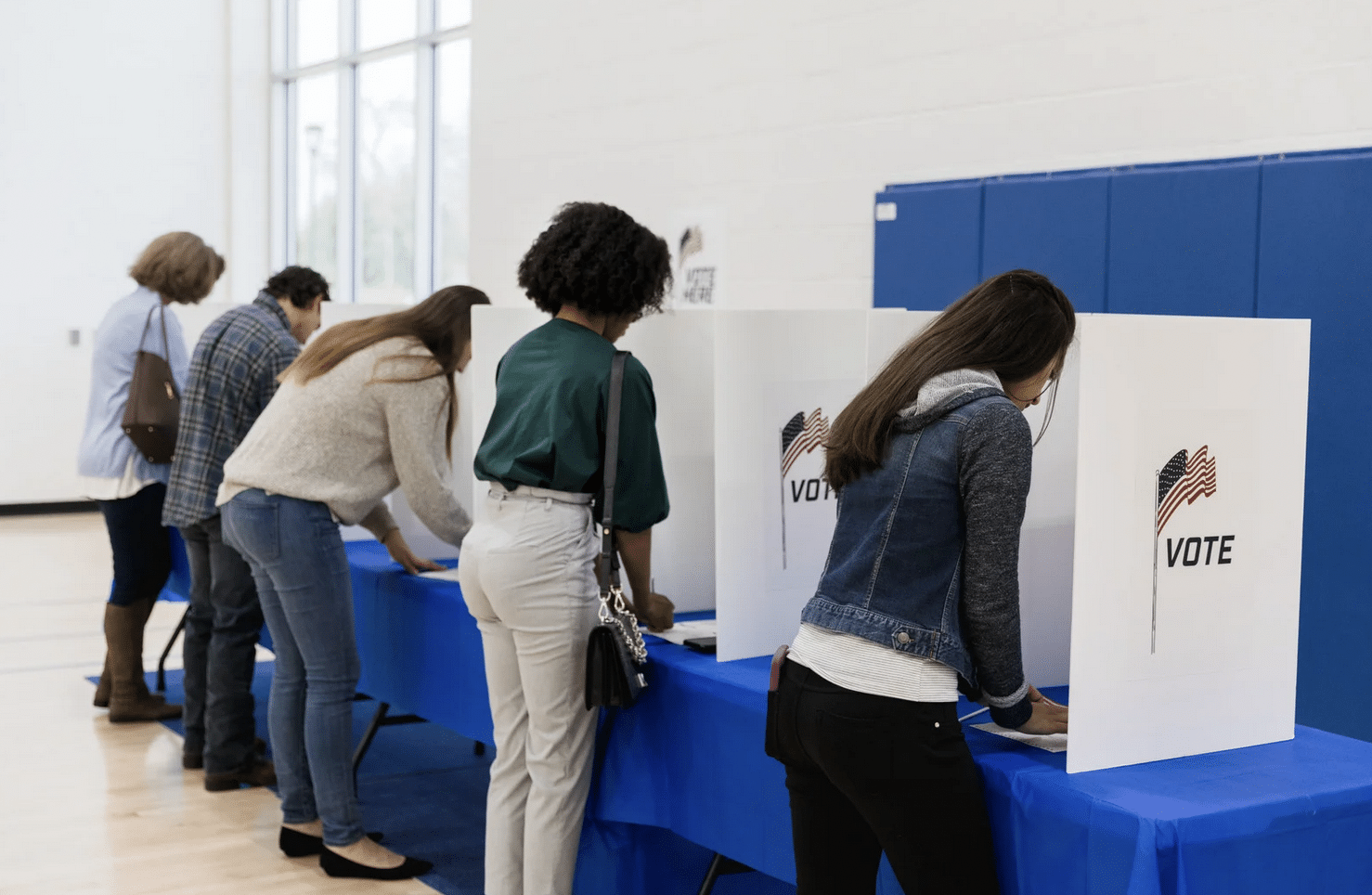

Every American deserves a voice in the decisions that shape their life, no matter where they live. Ensuring that rural voters have equal access to the ballot is about fairness, freedom, and sustaining a strong democracy for generations to come.

Rural Americans—about 20% of the US population—face persistent challenges to making their voices heard at the polls. Geography, culture, and history shape these barriers, but the impact is consistent: a 2023 study found rural voter turnout is roughly 5% lower than in urban and suburban areas. One-third of rural counties reported turnout rates below 60%, compared to 22% of the non-rural counties. There are clear linkages showing that underrepresented groups at the ballot box are less likely to see their preferences reflected in local, state, and federal policy, even if there are also other considerations at play. Given the interconnectedness and interdependence between rural and non-rural places, it’s crucial that rural interests are represented in policymaking.

Long-term policy choices, economic disinvestment, and institutional structures have restricted access to voter information and the ballot box. Because these barriers were constructed, they can be dismantled. Expanding reliable public transportation and internet access, as well as ensuring nearby polling stations, are among the steps decision-makers can take to increase rural voter turnout.

Bringing the Ballot Closer to Rural Voters

In many rural areas, residents must travel long distances to reach essential services, including businesses, healthcare centers, employment opportunities, and polling sites. More than half of rural polling sites serve areas larger than 62 square miles, compared to an average of just 2 square miles in urban communities.

Distance directly affects participation. Research shows that each additional mile between a voter and their polling place can reduce turnout by up to 0.99 percentage points. In some communities, travel distances have grown rather than shrunk. Halifax County, North Carolina, has reduced its number of polling places by 24% since 2012.

Similar patterns are seen nationwide: during the 2022 elections, residents of Kaktovik, Alaska—a remote village of 189 people—were unable to vote when the state failed to staff their polling site, and members of the Fort Peck Tribes in Montana had to travel up to 60 miles after being denied a satellite office.

Strengthening Daily Services to Support Civic Participation

Some daily services not typically considered voting infrastructure can have a significant impact on voter turnout when they are insufficient. Rural areas receive less funding than urban counterparts, which, as Keith Gennuso of the Population Health Institute notes, results in “lower access to broadband internet, libraries, parks and recreation facilities, and slightly lower access to adequately funded schools.” These spaces and tools are often used to host voter registration drives or town halls—activities that foster engagement and political belonging. When they are absent, the opposite effect occurs. A 2016 Pew Research study found that connection to the community is highly correlated with strong news consumption, which in turn is highly correlated with regular voter turnout.

The broadband gap between rural and non-rural regions highlights how access to basic services affects civic engagement. In 2017, only 73% of rural Americans had access to broadband speeds of at least 25 Mbps, compared to 98% of urban residents. Rural and lower-income households lag the national average internet subscription rate by 13 percentage points, and FCC data show that more than 26% of rural residents and 32% of those in tribal lands lack access to fixed broadband at 25/3 Mbps speeds, versus just 1.7% in cities. Without reliable broadband, rural voters lose access to online voter registration, ballot tracking, and media outlets that inform electoral decisions.

Reliable mail service is another daily infrastructure component that can expand civic participation when strong, but is often inconsistent in rural areas. Some Native nations receive mail only a few times a week, and rural post offices are sometimes open for limited hours. In Missouri, rural residents report frequent delays or missing deliveries. While vote-by-mail is widespread and even mandatory in some jurisdictions, many states still restrict it with outdated requirements such as “excuses” for eligibility or burdensome ID and signature verification rules. Expanding mail voting in rural counties has been associated with substantial increases in turnout.

As the digital age reshapes both communication and voting habits, gaps in services like broadband and mail delivery risk widening disparities in political participation. Ensuring equitable access to these foundational resources is integral to strengthening democracy in rural regions.

Trust – an Invisible Barrier

Years of chronic underinvestment have created structural gaps that are compounded by a crisis of trust. Extractive industries, such as mining and logging, have extracted wealth from rural communities for decades, and political inaction has eroded confidence in elected officials and institutions. Many rural voters now feel alienated from and distrustful of the very systems meant to represent them, and don’t think their vote will lead to positive change.

The dynamic becomes cyclical: underrepresentation of rural interests leads to voter disengagement, which reduces turnout, weakens accountability, and results in further disinvestment.

What’s Different in Indigenous Communities?

Barriers to voting are often uniquely layered for Native American communities. While many challenges facing rural communities also apply to Indigenous communities, additional obstacles make participation even more difficult. States often reject registration forms without a physical address, despite knowing that many reservation residents rely on PO boxes or shared delivery points. Many Native nations don’t receive full mail coverage, which can render voter registration, vote-by-mail, and ballot delivery nearly impossible.

In some states, Native voters have been told they must travel to towns where they have experienced racial harassment or discrimination in order to cast a ballot. Distrust of non-tribal officials is often deep, rooted in decades of harmful policies and practices. A survey of tribal members in Nevada and South Dakota found low confidence that their votes—particularly mail-in ballots—would be counted, especially when election officials were not Native. This distrust, combined with structural barriers, further depresses Indigenous voter participation.

Indigenous voters are also frequently excluded from polling and research datasets. Supporting Native nations’ data sovereignty efforts is essential to increasing participation. Collecting accurate, community-driven data on Indigenous voter turnout and the barriers they face is a necessary step toward ensuring equitable access to the ballot.

Solutions

Improving rural voter turnout requires strengthening the infrastructure that supports democratic participation. Accessible balloting, reliable transportation, expanded broadband, and funding for community centers can reduce some barriers. These investments should be designed for long-term resilience to ensure access for future generations. As election officials implement new measures to expand voting access, they should also clearly communicate how these measures protect vote security, reinforcing trust in the system and encouraging use.

Rebuilding trust in civic leaders is equally critical. Aspen CSG’s Thrive Rural Framework emphasizes developing local leadership and ensuring that communities have a meaningful voice in shaping elections and broader governance. Listening to concerns about extractive policies and advancing sustainable, asset-based development can strengthen trust in government. When residents see their input reflected in leaders’ actions, trust grows—and with it, civic engagement.

A special thank you to Aspen CSG’s 2025 summer intern, Cam Scotch, who led the research and writing process for this blog!