View this Publication

For key takeaways, see the Executive Summary. And for useful resources for measuring rural progress, see the accompanying Annotated List of Resources.

Introduction

Today, we have a generational opportunity to strengthen both prosperity and equity in rural communities and Native nations in the United States.

The billions of dollars made available in COVID recovery funding, as well as the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, are historic. Should a version of it pass, the potential $1 billion or more in the proposed Rural Partnership Program would provide sorely needed flexible resources for strapped rural and regional development collaborations. How the Economic Development Administration designs and makes decisions about the distribution of its unprecedented and significant increases in program funds, and how the Rural Development title is crafted in the likely 2023 Farm Bill reauthorization, among other legislative and administrative developments, may present additional opportunities to help communities and Native nations across the rural United States take the reins to strengthen economic, social, and health outcomes across their regions.

Likewise, several phenomena of the times have increased attention to rural populations, places, and businesses. For one example, the ravages of COVID and the opioid epidemic have raised consciousness about the worsening state of rural health and health care relative to urban. On the other side of the coin, fostered by the draw of outdoor recreation and family-raising quality of life, in recent years, more people have moved from urban and suburban to rural places, which was further bolstered by the COVID-induced reality that many occupations can now work from anywhere. That phenomenon has both spotlighted the value of rural living and raised its cost, increasing hardships for lifelong rural residents and essential workers who can no longer afford it.

In addition, the results of the 2020 Census, coupled with the growing cognizance of economic, social, and power inequities that have resulted from historic discriminatory practices, have raised awareness that one in four rural people are people of color – and that they account for the largest segment of growing or stabilizing population in many rural communities. Media coverage of these and other developments has piqued the interest of more foundations and individual investors, plus greater focus from the state and federal program levels, in rural community and economic development.

Any increased funding that accompanies this attention is necessary and welcome, but far from sufficient. Increased funding through the same program “pipes” will likely only give rural America more of the inequitable outcomes it has already experienced. So, some program redesign is required. Also required is a fundamental reassessment of how we measure rural development progress and success and who gets to decide.

If we get this reassessment right, the funding pipeline from all sources – federal, state, philanthropic, and private – will have far greater impact, especially for our most isolated and/or disenfranchised rural and tribal neighbors. And considering the rare confluence of resources and attention in play, we must measure up to the opportunity before us. We must measure what matters to rural people and communities, based on their deep knowledge and lived experience about what will best deploy their many assets to successfully address their localized opportunities and challenges.

This Call to Action amplifies the voice of 46 community and economic development practitioners from across rural and Native nation communities in the United States who make that case. It is offered as a tool to open and deepen conversations about better ways for funders and investors to design programs through which rural community and economic development practitioners and collaborations have the flexibility and power to decide what is most important to take on right now, what progress looks like, and how to measure it.

Participants and Structure

This Call to Action is the result of the first Thrive Rural Action-Learning Process (TRALE). The objective of each TRALE process is to quickly tap on-the-ground insights and experiences to help generate some breakthrough thinking about what works and what’s needed to push policy and practice toward increasing well-being for more people and places in rural communities and rural Native nation areas across the country, especially in areas of concentrated poverty.

The Aspen Institute Community Strategies Group (Aspen CSG) conducts each TRALE process, working with a varying set of collaborating partners. In each TRALE process, Aspen CSG asks approximately 50 rural doers, practitioners, advocates, and innovators with grounded knowledge to answer a specific question important to advancing action that will increase rural prosperity and equity. The conversations with TRALE participants around each question take place in small groups of four to eight people each over a short period, no longer than two months.

For this first TRALE process, Aspen CSG convened a total of 46 seasoned rural economic and community development practitioners from rural and Native nation communities across the United States. Each participant was recommended by national and regional organizations with deep engagement in rural America, including, in addition to Aspen CSG, the Rural Community Assistance Partnership, the Housing Assistance Council, and Rural LISC, among others. Aspen CSG invited recommended participants and offered an honorarium for their preparation and participation in the TRALE discussion. Each TRALE participant joined one of eight two-hour discussions with between four and eight people each in August and September 2021. The TRALE 1 participants work in many of the nation’s nearly 2,000 rural counties. (Of the nation’s 3,142 counties, 1,976 – 63% – are classified as rural.)

Collectively, the diverse participants account for hundreds of years of experience in rural economic development, community human services and health, housing, transportation, small business development, family asset building, development finance, grassroots community engagement and advocacy, and regional development. They are respected, committed leaders in their communities. See the bottom of this webpage for the list of TRALE 1 participants.

TRALE 1 Focus

Measuring Rural Development Success

Each TRALE 1 engagement addressed the issue of what indicators and measures should be used to signify short- and medium-term progress – and longer-term community and economic development success – for rural and rural Native nation communities. Participants were asked to share their own experience and ideas to answer two specific questions:

- What do we need to measure to truly indicate progress at increasing prosperity and equity in rural places and populations over the short, medium, and long term?

- What will it take for public, private, and philanthropic systems and investors to value, organize around, and use those measures?

Participants were asked to keep the following context points in mind as they prepared for the TRALE discussion – context that made the two TRALE 1 questions timely and important:

- For decades, rural community and economic practitioners have maintained that many indicators or measures of “success” that government, philanthropic, and private programs and investors ask them to produce and report are not well-suited or relevant to rural places. In some cases, investors are looking for raw aggregate numbers to show scale of impact, which always places rural investments at a disadvantage to urban options; in others, investors focus too narrowly on immediate job creation, dollars leveraged, or financial return-on-investment rather than the critical human, organizational, civic, and environmental ingredients that are fundamental to producing jobs and financial return over a longer term.

- We are in a “moment” of increased attention to rural places and people, and of increased will on the part of government and philanthropy to examine (and potentially adjust) their practices and policies to better serve rural, advance rural prosperity, and strengthen rural-urban connections. In both government and philanthropic circles, some leaders are asking: “What should we be measuring in rural? And how can we do it?” We want to help provide useful answers to meet this opportunity.

The TRALE 1 participants contributed an abundance of rural development experience and knowledge, far more than could be included in a report focused primarily on measuring rural development progress and success. But, before detailing the six primary measurement principles that emerged from their exchanges, it is important to note two significant context issues that are important background to help understand working in rural America.

The Community Challenge of Using Quantitative and Qualitative Data

The inadequacy of federal data was a recurring theme in many TRALE sessions. Because of the lower density in rural areas, the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey provides only a five-year rolling average for key demographic data in many rural counties and sub-county areas. This is inadequate for developing or evaluating programs that focus on producing results over one- or two-year time frames. More up-to-date statistics are collected and released annually or more frequently by the Department of Labor and the Bureau of Economic Analysis, but for rural areas—especially sub-county rural areas—these can be limited by data privacy requirements. When examining data from small geographic areas, outlier households and businesses can be easily identified; to maintain privacy, that small-area data is often suppressed.

In 2020, the Urban Institute, Housing Assistance Council, and Aspen Institute Community Strategies Group released In Search of “Good” Rural Data, a report that details the challenges of securing and using reliable quantitative data in rural and Native communities. That report also notes emerging data sources and methods, such as proprietary private data and new national surveys. Practitioners highlighted the need for improved qualitative measurement methods and best practices to better capture community conditions and perspectives.

Native Nation Realities

Native nations are mostly rural in setting, but culture, governance, and historic and ongoing oppression make their realities distinct from the rest of rural America. Aspen CSG’s Native Nation Building: It Helps Rural America Thrive outlines the historic oppression, cultural distinctions, and sovereignty that shape these unique conditions, as well as the nation-building strategies necessary to strengthen Native culture and prosperity while linking those efforts to broader rural development. TRALE participants from Native nations—deeply knowledgeable about their communities and histories—emphasized these distinctions while contributing insight and resonance to the TRALE findings overall.

As Lakota Vogel put it: “It really is important to understand that the difference between rural America and Native America is that we’ve been through a forced assimilation…where the government was hoping we would just melt away into the fabric of America.” Others noted issues of data sovereignty and the importance of understanding that tribal lands and communities are not like civic municipalities. Pamela Standing explained:

“People don’t understand when they work with us; they treat us like we’re a municipality and that we have access to all these resources that a township or city or municipality has. We don’t have access to those resources. We are in the process of building the legal and physical infrastructure that we need to grow a diverse and thriving economy in our communities.”— Pamela Standing, Minnesota Indigenous Business Alliance

Participants also pointed to the decades of determined Native effort to rectify injustice and exercise sovereignty, now growing in strength. Pamela Standing noted: “I heard an elder say something once. I’m going to probably say it wrong, but she said “‘They didn’t realize when they tried to bury us that we were the seed, and, you know, so we’re still here.'” Weaving these realities of Native history, conditions, culture, organization, and assets is critical to advancing both Native and rural prosperity in any region.

Six Principles for Measuring Rural Development Progress

- Expand the range of individual and community assets used to indicate critical rural development progress.

- Do not dictate what to measure. Work with rural initiatives to define the progress indicators that make local – and mutual – sense.

- Measure progress relative to the rural effort’s starting point at its current stage of development – not against an ideal “success” standard.

- Measure decreases in place, race, and class divides – and increases in the participation and decision-making that reduce these divides – as inherent elements of increasing rural prosperity.

- Identify, value, and measure effective collaboration as progress toward rural prosperity.

- Identify, value, and measure signals of local momentum as progress toward rural prosperity.

Principle One: Expand the range of individual and community assets used to indicate critical rural development progress.

Rural and Native nation communities are astonishingly complex. This is counter to conventional thinking that life is simpler, that it is less expensive to live, and that things are easier to change and accomplish in rural places than in urban areas. None of these stereotypes is typically the case.

One thing that may be easier in rural places is to quickly and clearly discern the connections and the impact that action – or inaction – on one issue or condition has on other issues and conditions. Rural development practitioners are quick to note, for example, when regional educational institutions offer training regimens for job skills that are a mismatch with what local employers demand, or when lack of transportation or childcare for workers is the true impediment keeping local people from attaining better jobs or hindering local employers from expanding. Likewise, they can see the difference that one key change – for example, a Main Street building restoration, the resurgence of an annual festival that draws outsiders and sparks youth participation, the start of one new locally owned enterprise, the creation of a dozen new childcare slots, the clean-up of one eyesore or environmental hazard, the presence of a circuit-riding doctor or dentist one day a week in the community, or a few workforce housing energy retrofits that improve family bottom lines – can have on moving things in a new direction across a community.

These “asset changes” are often critical preconditions to achieving the more conventional and longer-term measures that many public, private, and philanthropic funders require rural projects to report as “development progress.” Those more conventional measures – for example, the number of new jobs, the volume and extent of loans, or return on standard investments – are often inappropriate in rural communities. This is especially true in places that have, for example, been historically left out or discriminated against, that need prerequisite skill-building, or that must address other community, family, or worker priorities first. These other “asset changes” are thus more important and useful measures of progress during some stages of rural development. And, unless they are accomplished, the more conventional measures of progress may never be in reach.

Many funders stick with the conventional measures for understandable reasons. Data on them may be more easily or universally available across place because it is collected nationwide by government sources; thus, it is easier to aggregate “impact” across a set of a funder’s investments if each funded effort is required to report on the same publicly available indicators. In addition, reporting easily countable and tangible things like jobs created and loans made makes it easier for leaders to claim or assign credit for success.

Rural development practitioners are asking for flexibility to allow and use a broader, more holistic set of community and economic development progress measurements. Doing so encourages local analysis that drills down to a place’s specific economic sectors and geographies, that identifies the real factors that stand in the way of next-level progress, and that gauges whether supports and systems are in place to catalyze and sustain longer-term progress. Over just the course of the eight TRALE group discussions, practitioners suggested numerous alternative economic and community metrics.

For example:

- The stock of year-round, locally owned housing

- Change in school enrollments

- The number/ratio of disconnected youth

- Increases in post-secondary educational attainment

- Labor market participation rates

- Changes from an accurate baseline in the number and growth of locally owned enterprises

- Business longevity and growth rates

- Growth in high-wage/high-demand sectors

- Changes in race, ethnicity, and gender wage gaps

- Affordable child care slots compared to demand

- Community college alignment with the local economy

- Aligned continuum of family services

- Entrepreneurial growth as voluntary or involuntary (Is self-employment only an emergency response?)

- Dollar leakage in or out of the community

- Change in air, water, and housing quality

- Economic and social impact of job retention

- Living wage requirements – and living wage job availability – in a region

- Change in household savings rates

- Broadband coverage to homes rather than broadband “coverage” only on Main Street

Other practitioner exchanges have offered many more, and more targeted and intensive consultation and research would do the same.

The TRALE process also surfaced that, despite often rigid reporting requirements, some practitioners are voluntarily submitting supplemental measures to their funders that better reflect reality on the ground. Cheryal Lee Hills of the Region Five Development Commission (R5DC) in rural Minnesota offered this approach:

“It’s important to challenge systems that have been entrenched in Congress, our state agencies, or foundation partners that say, ‘This is how you’re going to measure success.’ We’ve been taking the approach where our team will measure what the agencies or foundations want and we will measure what our communities care about. We then give the funders both – in hopes they will see that both qualitative and quantitative matter and will evolve into better measures of success.”

Cheryl Hills, Region Five Development Commission

R5DC organizes its “what my community wants” measures around eight categories of community assets, derived from the historic “community capitals” research that is incorporated and expanded in the WealthWorks approach to rural development. Their Minnesota Region 5 Development Commission WealthWorks Evaluation framework can help individuals and communities set development priorities and offer clear and relevant metrics of progress. Their practice illustrates the value of using well-designed, well-researched frameworks to set priorities and measure true rural progress.

“Increasing or maintaining the balance of locally owned businesses – that’s the root of local wealth. In so many distressed rural areas, there has been this great outsourcing. The hardware stores, grocery stores, hospitals, many major employers, even the newspapers are now owned by corporations outside the community. In some cases, this has kept these services available, but the collective effect is that all this outsourcing has become like a vacuum sucking local wealth and power out of rural communities. It impacts jobs, wages, philanthropic giving, services, pride of place. In the PA Wilds we are trying to counter this by focusing on building rooted local wealth through entrepreneurship. It would be great to see more focus around local ownership and the multiplier effect it can have on rural communities.”

Ta Enos, PA Wilds Center for Entrepreneurship

“One of the measurements that we have used to track ourselves was [heirs’-property ownership] titles resolved, and one of our funders kept saying ‘Well, is that all you guys are doing?’ And we’re like, ‘But do you recognize how much time and energy – and how much education – we’re providing to families just to get them to that point?’ It is an education moment for the nonprofit to help [the funder] understand the complexity of the work that you are providing and try to convince them.”

Jennie Stephens, Center for Heirs’ Property Preservation in South Carolina

“Most Community Action Agencies operate LIHEAP (Low Income Home Energy Assistance) programs … but who actually benefits? Yes, the families benefit because they have a portion of their light bill paid. But has anything changed? Or are they not going to need assistance in three months or four months? But who gets the cash? The utility companies. Same with these rent assistance programs, yes, we are helping to prevent massive numbers of evictions. We don’t talk about the fact that while some landlords are huge corporations, others are a small local business that may own one or two or three rental homes…and we help them prevent foreclosure on properties for which they still have mortgages or we help prevent them from having a significant decrease in their income as a result of their tenants not being able to pay their rent… [Some policy-makers]…focus on the deficits of the families that we serve rather than recognizing where the cash is actually going.”

Terry Bearden, CCAP

“The data for Puna says that 78% of households are ALICE (Asset-Limited, Income-Constrained while Employed) and in poverty. A woman from Puna told us, ‘We might be the worst when it comes to income, but we are the best when it comes to ‘ohana (family): None of us are making it on our own, and all of us are making it because of ‘ohana.’ The definition of wealth for Hawai’i Island communities is very different from what’s being presented to us as a measure of success.”

Janice Ikeda, Vibrant Hawai`i

Recommendations

Government

- Become familiar with and accept frameworks that value community and development progress as evidenced by changes in diverse forms of capital and assets – and their preconditions.

- Push boundaries and creativity to expand the menu of measures for what can qualify as progress or effectiveness for rural initiatives funded by your program, agency, or department – or, better yet, across your government sector (local, state, or federal).

- Measure assets and opportunities as well as needs. A distorted view of people and place happens when expectations result in bias that sees only needs or deficiencies. Fully recognizing community assets leads to a more accurate picture of rural

- and tribal conditions. This recognition is a precondition for establishing a respectful and productive partnership.

- Design solutions to address the inherent limitations of federal data for communities and Native nations across the rural United States. The American Community Survey of the Census Bureau, a major data source, has limited utility in measuring changes in rural places.

Philanthropy

- Everything in the Government section, plus:

- Engage in an ongoing dialogue with government funders about expanding and improving progress metrics for rural community and economic success. Some philanthropic funders have a more creative, flexible approach to measuring rural community change. While there are inherently different demands on public funders for accountability, a sustained dialogue between philanthropy and public funders could hold great promise to advance the field and yield better rural community progress and outcome measures.

- Formalize a field of practice around innovative frameworks to measure and mark true wealth and asset building. The TRALE discussions demonstrate just a small portion of the tremendous stock of experience and knowledge across rural and Native

- communities. Practitioner peer-exchange – and mining it to inform better measurement typologies and practices – could be maximized through supported, systematic opportunities to link, learn, and improve practice together.

- Support local nonprofits and governments to document qualitative methods that better illuminate ground-level success. Improved methods to standardize and deploy qualitative data for measurement can contribute to richer local and regional insights – as well as cross-place and field-wide learning, practice, and narratives.

- Support training for local and regional development organizations to assess and deploy alternate data sets or community-change frameworks tailored to the priorities of local stakeholders.

Rural Practitioners

- Familiarize yourself with community and economic development frameworks for measuring multiple assets and aspects of rural development progress. Reflect and adopt what’s useful to shape productive local strategies and measurement approaches. Form regional and grassroots measurement partnerships to expand impact and grow the field.

- Have confidence that you know your community. Just because you may have little access to strong quantitative data (or may not feel comfortable using it) doesn’t mean that you don’t know what counts, or that what you know doesn’t count, when compared to somebody else’s “hard data.”

- Firmly but diplomatically push back on external funder metrics of progress and success if they don’t meet your community’s reality. Keep speaking the truth as you see it. Use reporting as a “funder-teachable moment” by adding local measures that you think are as (or more) important than what funders require.

- Engage often and regularly with state and federal elected and appointed leaders. Invite them to your community to show them your realities; host sessions between them and your philanthropy stakeholders to ground them in your local realities. Numerous TRALE participants noted they have found it important to do this to help government and philanthropic leaders understand your reasoning behind measuring what’s important to your community.

Action Story 1: You Get the Multiple “Whats” You Measure

When a community targets and measures results related to the full range of its priorities, it is better positioned to make and show impact across multiple systems.

The Aspire Program, which links workforce development, local housing, and family financial counseling, was created by the Northeast Community Action Corporation (NCAC) in rural Bowling Green, Missouri, in partnership with the Missouri Department of Corrections and the joint apprenticeship program of the Carpenters Union.

Through Aspire, incarcerated individuals learn and receive certification in carpentry while they build homes inside a local correctional facility that is located in the NCAC’s region. Participants reenter the community with marketable job skills, which increases their odds for living a productive life with dignity and reduces recidivism.

According to Carla Potts, Deputy Director for Housing Development, “Too many times prisons are trying to [train for] things that, when [individuals] come out, are not marketable skills. So [with Aspire], they’ll come out with skills and with links to jobs, and then they’ll enter the Union to become a journeyman carpenter.”

Aspire’s system connections deepen its impact in the community. The new homes are moved out of the correctional facility to provide housing stock for lower-income households in the area. The buyers receive financial fitness and homeownership counseling to qualify them for loans sourced from USDA that do not require a down payment.

“The only way I know that most people build equity is through a home,” said Potts. “A lot of people don’t have that opportunity or think they can’t, so these will be homes that will be less expensive, but they’ll also be homes that can come back out into the community, and help with the housing stock, because we have a serious issue with housing in our communities. So, we’ll measure in a number of ways, we measure training first, then jobs, and then we’ll measure housing and homeownership and building equity into communities.”

By focusing on those multiple indicators from the start, the Aspire effort helps leverage systems and collaboration to increase community vitality.

Principle Two: Do not dictate what to measure. Work with rural initiatives to define the progress indicators that make local–and mutual–sense.

A constant theme heard from practitioners during the TRALE group discussions was that, frequently, funders, besides having a limited definition of success, envision estimates of what will constitute progress over a funding period that do not reflect community reality.

So, as a necessary companion to the first measurement principle, it is important that the rural community, region, or initiative do the defining, in relation to the community’s context, knowledge, and objectives, of what will constitute success markers over the time period of funding. Defining tangible outcomes must fulfill a community’s vision and understanding of necessary steps toward success – steps that at the same time can be understood as necessary to move toward a funder’s desired longer-term impact.

This is best done in conversation, and in relationship, where local knowledge is honored, and power is shared between rural initiatives and their funding or investing partners. Only the understanding that comes from discussing the reality that each party – both the rural effort and the funder – is facing will lead to the kind of flexibility that rural communities need to make holistic progress, and that funders need to change their own systems to keep them from locking rural communities, especially disadvantaged rural places, out of the opportunity for critical funding and investment.

Models show this can work. As Joe Short of the Northern Forest Center reported:

Our most productive funder and investor relationships are where we are mutually focused on the outcomes that we’ve defined in terms of community well-being, and where there’s flexibility in terms of the outputs that they’re looking for along the way. – Joe Short, Northern Forest Center

Rural practitioners also advise extending the application of this principle to a funder’s reporting requirements. Funders often require extensive extraneous data for reports that are time-consuming, extractive, and inhibit grantee effectiveness. For rural organizations, this can become an administrative burden. Even when they have only one demanding funder, short-staffed rural organizations can find that reporting requirements eat up a disproportionate – and unanticipated – amount of their budget. This is compounded for larger rural initiatives with numerous funding sources, when their varying funders for the same initiative require different measurement or data reporting using different indicators and different systems.

The question for both parties to answer together is: What really matters to measure, now, at this moment of action? Many foundations are becoming more sensitive to “walking with” rural initiatives to negotiate what success over the course of a grant or investment will look like and how to measure it; some even logically check in to mutually assess progress and make mid-course corrections on the effort’s implementation, output, and outcome expectations. Doing the one-on-one “retail” work of negotiating with rural initiatives is a steeper hill for state and federal government to climb, but surmounting it is essential if we are to steadily extend and deepen rural prosperity, especially in the most historically and economically challenged rural and Native nation communities.

“There has to be mutual respect, and I think oftentimes communities value what funders bring to the table because of the connection to the financial resources that will come along with them. But that same respect isn’t always given or shown by funders who walk into a space acknowledging the [local] work… If you don’t demand that, it doesn’t happen.”

Felecia Lucky, Black Belt Community Foundation

“It seems to me that in rural communities there may be a different quality of conversation about what matters, because of the strength and importance of our social network and our quality of life, more so than how much someone makes, or their status.”

Ajulo Othow, EnterWealth Solutions

“There has to be mutual respect, and I think oftentimes communities value what funders bring to the table because of the connection to the financial resources that will come along with them. But that same respect isn’t always given or shown by funders who walk into a space acknowledging the [local] work… If you don’t demand that, it doesn’t happen.”

Stacy Caldwell, Tahoe Prosperity Foundation

“It’s much more likely that measurement is going to get done if you find ways for the community to assess itself and to understand what they can do to move forward. Your first thing is small wins, knowing this is iterative and a long game. The second thing is: use trusted and research-based measures that are focused on the vitality of communities and communities that have made it. What I am getting to is this idea of being unapologetically local about measurements, because if it’s not improving the local place and the people doing the work, then it is super extractive.”

Heidi Khokhar, Rural Development Initiatives

Recommendations

Government

- Work with grantees/awardees to understand their varying contexts at the front end. Rural communities in different historical, economic, cultural, and geographic contexts can rightly value different factors as indicators of progress towards an outcome valued by a funder. Engage in a dialogue with rural and tribal development practitioners on the front end of an award or grant to understand what reality looks like on the ground and build shared consensus on desired outcomes.

- Together, select and customize useful and realistic metrics of community progress that make local sense. To determine required reporting requirements, negotiate and agree on indicators and measures toward mutually desired outcomes that are realistic in the local context over the funding time period. Use a broader menu of development progress indicators to help advance the discussion.

- Ask for, accept, and learn from any (optional) supplemental community-driven metrics. Encourage rural initiatives to report other measures or indicators that they think — or discover — are important. Analyze these across the portfolio to spark new thinking about measuring progress and to add to the menu of potential progress indicators.

- Conduct constructive mid-course consultations. Every project and initiative encounters unexpected bumps along their planned path, some that propel or slow their speed, and others that change their direction. Engage grantees and awardees at meaningful intervals to see how things are going, for the purpose of adjusting strategy and tactics, along with progress expectations.

- Discard data reporting requirements that are not useful for project implementation, impact, and learning. Native and rural grantees will be more productive when they can jettison extraneous, non-relevant data requirements.

- Emphasize grant selection and monitoring criteria over data collected to control fraud and misuse. Though they are critical to meet legal requirements and prevent corruption, over-emphasis on collecting information to gauge fraud and misuse can crowd out the data useful to understanding rural situations — and can even inhibit rural places from applying.

Philanthropy

- Everything in the Government section, plus:

- Support efforts by rural initiatives, governments, and nonprofits to encourage public funders to adopt innovative, community-driven program metrics. In addition to direct engagement with public funders, use philanthropy organizations and affinity forums and convenings to open doors for rural and Native community practitioners to speak directly to public funders and policy-makers.

- Support intermediaries to develop practical, community-driven measurement approaches and protocols. Regional, rural, and national intermediaries can help examine ideas, experience, and practices across place and further develop community-driven measurement methods and models that would be more easily accepted by public, philanthropic, and private funders — and have more value for local rural initiatives and progress.

Rural Practitioners

- Advocate for and urge government and philanthropy to engage rural communities and practitioners in defining measurements toward rural prosperity — and accepting them. Show up in legislative and program design settings where rural and Native community and economic development are being discussed. Share your stories about what progress looks like — and the importance of community voice and agency in defining meaningful and productive measures.

- Start the negotiation. If the funder does not do it, when possible, set up an in-person or virtual conversation with a funder during the application process or at the front end of a grant or award to negotiate and establish indicators, measures, and reporting requirements that are useful, realistic, and doable for you.

- Report it anyway. Even if the funder did not require or accept it, report indicators and measures that you think are truly important and indicate progress — and explain why.

- Make some measurement noise on funder feedback and evaluation surveys. Make sure you include specific and actionable ideas on how to change and improve measurement and reporting requirements when given any opportunity to provide public, private, and philanthropic funders with feedback.

- Press philanthropy and field intermediaries to give you the support you need to measure better. Talk to peers about common conditions and concerns. Collaborate to pitch ideas that funders might support to develop better measures and measurement systems, and to support the work it takes for you to measure.

Action Story 2: Changing Minds: The First Order of (Changing) Business

High-impact outcomes can require a readjustment of mental frameworks for communities as well as funders. McIntosh SEED, located in rural Georgia but working in several southern states, has a long history of “walking with” communities to see new possibilities and grow their capacity

High-impact outcomes can require a readjustment of mental frameworks for communities as well as funders. McIntosh SEED, located in rural Georgia but working in several southern states, has a long history of “walking with” communities to see new possibilities and grow their capacity to succeed. In Mississippi, they partnered with local Black farmers to generate more income from their landholdings.

“Mindset changes have to happen first for communities to succeed,” according to John Littles, McIntosh SEED’s executive director. He notes that the rural Mississippi farmers were growing what they had traditionally grown, but it wasn’t generating income for those growers. “We connected the farmers with buyers and wholesale buyers, and they had a demand for a [different] specific crop. So, the farmers started growing for that demand.”

That was an economic change in them: Mentally, the shift was “Well, we’ve always grown corn, but there’s not a market for corn; buyers want carrots, or they want squash.” Internally and in their community, they are accustomed to growing what they always have; they inherited that tradition. So, it is important to measure those types of mindset changes, seeing the business side of it, not just seeing that they like to grow what they have grown in the past.

Littles reflected on the importance of supporting communities to change their mindset about what is possible as a precondition for other desired outcomes. “How do you stop relying on local government to change something in your community when you, you are the change makers in the community? I think most importantly, there has to be ongoing support for that and getting them in a space where they’re comfortable.”

Principle 3: Measure progress relative to the rural effort’s starting point at its current stage of development – not against an ideal “success” standard.

Every community has distinctive assets. And in each community, each asset is in different shape, depending on its quantity and quality.

For example, two rural communities may have the same access to plentiful water, but one community’s water may be safe to drink, while the other’s may not. Two rural communities may have similar broadband availability, but in one, there are people ready with jobs and training awaiting, and in the other, no one is ready to step into jobs. One region may have a very capable, collaborative, multi-community development organization with a good track record, while another has a small, isolated, under-resourced, single-issue group struggling to stay afloat.

When rural community and economic development work is launched, this variability matters for design and implementation, but also for the pace at which things can happen. “Apples to apples” comparisons do not capture or respect those unique conditions in the community taken together, nor the capacity of the organizations implementing projects that aspire to those conditions changing, by the end of the period of a capital infusion. A principle of measurement should be “first, do no harm.” When funding focuses only on rewarding “success” as measured by absolute numbers and not by relative progress, the funding and support infrastructure creates a bias against rural communities that are, by definition, smaller and take longer to produce large numbers, no matter their stage of development.

- Going for numbers – Many funders, whether public, philanthropic, or private, want their investments to tally up to large aggregate numbers. This drive for absolute numbers can harm rural places.

- Defining scale as raw numbers rather than ratios. The drive for “large numbers as impact” ignores how deeply a smaller result can benefit the place. No matter the size of the numbers, the real impact in the community can be great when progress is measured relative to that starting point.

- Bypassing the multitude of struggling “early-stage-of-development starting point” communities in rural America. Decades of underinvestment and discrimination based on geography, class, and race have resulted in low-resourced organizational capacity in many of these financially poorer rural and Native nation places; thus, many are now in an early-stage-of-development situation, working on improving the preconditions necessary before they can pursue and achieve “standard” development success measures. Investing in these rural places takes a non-standardized approach. Again, in part because development success too rarely is defined or valued as progress on these preconditions, poorer rural places gain less access to resources and to making meaningful progress.

As TRALE participant Ines Polonius, CEO of Communities Unlimited, noted:

“Community-centered measurement! Measure a community’s progress against itself, not against an elusive set of data points from somewhere else. And make the measures relative to the size of the community. [Even when] you do end up measuring jobs … in comparison to what? I’ve had folks say, ‘Who cares that you created 53 jobs?’ The community cares that you added three percent to the total number of jobs in that community! I think that if you took those relative measures and put them in an urban environment, they would gather more attention… right? So how do we do a better job of measuring like that?”

Ines Polonius, Communities Unlimited

When more communities assess and articulate progress from their own starting points, and funders begin to understand what that will yield across places with varying starting points, more progress can be made in advancing toward longer-term development success, especially in lower-wealth rural places and populations.

Of course, one key conundrum this presents for funders is how to measure, aggregate, and report progress or success across many rural places with many different starting points that are using many different asset measures.

One way to approach this would be to adapt the Whole Family Approach Life Scale (formerly called the Crisis to Thriving Scale), originally developed by the rural Garrett County Community Action Committee, which other Community Action Agencies (CAA) across the country are now using to help striving families set goals and measure progress based on each family’s starting point situation. This scale asks each family to self-report their current situation on multiple dimensions – financial security, education, health, housing, credit, social network, etc. – choosing from one of five stages (crisis, vulnerable, safe, stable, and thriving) for each dimension.

Using this scale, each family defines their own starting point and chooses their own priorities over, for example, the next six months or year, and they can mark progress on a clear set of indicators. The CAA programs using this scale can then aggregate by reporting how many families made progress on their goals overall, and on specific goals, while also collecting information on which dimensions need the most attention, which helps the CAA design and tailor their services to meet local needs. Conceivably, a similar scale could be developed for different asset dimensions for rural communities, regions, or initiatives that would allow funders to aggregate progress and impact across place, despite not every place working on or measuring exactly the same thing.

“I was a government funder for eight years in rural New Mexico, and I walked into communities thinking, ‘The poverty rate was X,’ or ‘This was the income level to get [to in] this program.’ And if I could have walked into a community knowing what that community felt was low income, or how to measure how they felt they were at, or their level of satisfaction with their economic situation, that would [have been] so much better.”

Terry Brunner, Pivotal New Mexico

“There’s such a lack of understanding that it’s going to be different for each community. A few years back, I was approached by a local entity that does community-based projects all over the world, but [not] necessarily in their own backyard. They wanted to do a project somewhere in one of the Native communities here in South Dakota – and it needed to be an economic development project. And I was so excited. We met for coffee and I shared an entire set of project ideas focused on Native artists. For context, 79% of our home-based businesses are arts-based, and roughly 51% of our people rely on a home-based business for income; that breaks down to about 40% of people relying specifically on art for income. They responded: ‘I think you misunderstood, we’re looking to do an economic development project.’ I thought, ‘Focusing on something that impacts income for 40% of the population isn’t economic development???”

Cecily Englehart, Dakota Resources

“How you perceive is how you proceed. I believe this and I witness misperceptions about Native America all the time. These misperceptions limit our opportunities and we use a lot of resources to break down these misperceptions just to get to a starting point with funders.”

Lakota Vogel, Four Bands Community Foundation

The Call to Action

Government

- Measure progress from community starting points, not predetermined program or agency ideals of success. What is achievable in any effort is dependent to a great extent on conditions, resources, and capacity at the start of any initiative. Respect the communities you work with by having them define their own starting points across critical dimensions.

- Be clear on the difference between measuring progress and measuring success. Setting and achieving realistic expectations for what short-term progress looks like from community-defined starting points will likely spur additional effort and progress toward longer-term prosperity outcome “success.”

- Take into account the time variable in setting progress expectations. Discuss with practitioners and initiatives what their realistic progress indicators and change expectations are over the period of the grant, award, or loan.

- Gauge rural progress as ratios in relation to the starting point in order to determine true impact. This is not only the right thing to do; it will allow for fairer comparisons with urban efforts. It will also help notice and learn from innovative rural efforts that are often overlooked or ignored because of low raw-number-results potential.

- Check for – and work to eliminate – program-design bias against initiatives starting at different stages of development. Evaluate department or agency procedures and standards for assessing community conditions, assets, and capacity. Assess whether program requirements keep initiatives in rural places that are at earlier stages of development – especially in distressed and historically disadvantaged situations – from applying or participating. Consider designing programs in tiers that make resources available for efforts at varying starting stages of development.

- Convene and collaborate – across government, private philanthropy, and rural development practitioners – to build consensus on frameworks and methods for defining community starting points.

Philanthropy

- Everything in the Government section, plus:

- Support and test innovative methods to assess starting-point baselines as well as conditions that signify progress at different stages of development. Partner with intermediaries, grantees, government, or others to create practical and useful “stage of development” scales – like the Crisis to Thriving scale – to help rural initiatives identify their starting point on multiple community and organization dimensions and set objectives for progress on priority dimensions over a set time period.

Rural Practitioners

- Know your own starting line. Develop a list of dimensions or factors that you think are important in describing the status of your community or region. Compile quantitative and qualitative data that describe where you are in relation to each factor. Use that to help your local stakeholders as well as funders understand your starting point – and as a baseline from which you can establish and gauge progress.

- Be a champion for your own starting line – and what progress looks like from that starting line. Be a champion for your own starting line – and what progress looks like from that starting line. Trust that you know your community. Color “outside the starting-line borders” that are set by others to articulate what progress will be for your effort at your stage of development.

- Report your impact as progress from your starting point. Employ ratios or percentage gains or changes in relation to your starting point in order to accurately portray impact on your local community, population, or economy. Do this whether or not it is requested.

- Carry out regular reassessments to gauge progress and to ensure that clients and communities are speaking clearly about local conditions, assets, and priorities. There are always new things to learn about and be surprised by in your community.

Action Story 3: Centering the Start… to Finish

Committing to priorities set by the people or places that a program aspires to help can be a critical step for project integrity and defining true success.

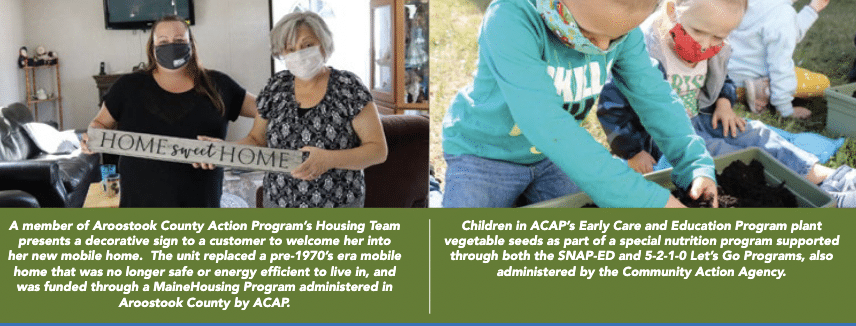

Committing to priorities set by the people or places that a program aspires to help can be a critical step for project integrity and defining true success. Adopting the Crisis to Thriving Framework for holistic family development was a four-and-a-half-year journey for Aroostook County Action Program (ACAP) in Maine – a journey that brought dramatic transformation not only for striving local families but for the organizations that embraced the framework.

The ACAP Crisis to Thriving Framework includes 19 different domains that are critical ingredients in moving whole families into stable and then thriving conditions (e.g., food security, housing situation, school readiness, financial management, transportation, childcare). Families select their priorities, indicate their current circumstances, and then, with supportive coaching, move through milestones from crisis, to vulnerable, and then onward to safe, then stable, and, finally, thriving status. By choosing what entry point and what they want to work on first, families are motivated to invest in the work that they know will be meaningful to them.

Jason Parent, executive director and CEO of ACAP, said of adopting the framework, “We were definitely swimming upstream because you’re not necessarily doing it with the initial blessings of funding sources. You’re having to prove that this is an opportunity.”

The hard work of organizing family engagement and measurement around the framework in the early years paid off during the pandemic. Parent described the impact: “I cannot imagine how our agency would have served our community if this pandemic had happened before we began this transformation, and before we began to look at how we work collectively across the organization and tap into all resources and truly put our customers at the center of the work that we do. I’ve seen the difference that it’s made in the lives of the families that we serve, but I also see the difference it’s made in the staff doing the work. Our staff should be wiped out, exhausted from the additional efforts that we’re doing with the pandemic right now, but they’re feeling that they’re making a difference in that measurable success in families’ lives.” Starting with a strong targeted framework that identified and honored local priorities became the foundation of their measurable success.

Principle 4: Measure decreases in place, race, and class divides – and increases in participation and decision-making that help reduce the divides – as inherent elements of increasing rural prosperity.

Just as in urban America, rural communities and regions are deeply concerned with strengthening the social and economic “middle class,” which has been in decline in recent decades as wealth inequality has widened and contributed to civic, cultural, health, and power divides.

In rural areas, discriminatory practices based on place factors (size and remoteness) combine and overlap with class and race (and often gender) factors. Historical place, class, and race discriminatory practices and outcomes have shaped the conditions in many of today’s most challenged rural and Native nation communities, increasing gulfs both within rural regions and between rural and urban areas.

Class

Declines and changes in key industry sectors such as mining and manufacturing have gutted the economic engines of many rural regions that once provided living-wage jobs for families across generations, often with good benefits and without requiring a college degree. The disappearance of many of these jobs – and their replacement with minimum (or less) wage jobs lacking benefits – has created or deepened poverty in many rural places, even for people working full-time (or more). At present, 85 percent of the 353 “persistent poverty” counties in the United States are rural – evidence of a deep class divide between rural and urban/suburban America overall.

At the same time, many rural areas with natural resource amenities have been attracting high-wealth families who have bought second homes or who, spurred by the work-from-anywhere COVID aftermath, are moving to rural areas full-time for quality of life. This influx of “have” newcomers has driven up the cost of living for the long-time rural residents who were already struggling, and has amplified the economic, social, and power distance between local haves and have-nots within rural places. Tax structures like mortgage interest deductions that preference the already wealthy, the design of key social programs that hinder mobility for the poor due to benefit cliffs or justice system strictures, and disaster recovery systems that distribute resources to the better-off communities first – all of these deepen wealth inequality in rural America.

Place

Place discrimination also affects rural areas. It is a function of dismissing small community size and geographic location or isolation, and of the cultural and demographic dominance of a nation’s population that is now 86 percent metropolitan (2020 Census). This domination is commercial, cultural, and often dismissive of the “flyover country” that is the primary source of food, materials, energy, water, and other resources on which the entire nation depends. This can make a dramatic difference in access to resources.

Place discrimination shows up in the qualifications and details required when applying for public, private, or philanthropic support or investment. For example, as described earlier, some funders require a population size or level of “raw number” expected outcomes not achievable in rural places, essentially locking rural applicants out; others require complex application and reporting information that low-resourced rural places and organizations with few staff or only volunteers struggle to manage. As a result, rural places, especially those most disadvantaged, “disappear” from the radar screen of funders and service providers.

In the nation’s low-density rural places, for example, health care is more expensive, fire departments are staffed completely by aging volunteers, and internet access is too often absent, substandard, or unaffordable.

Race

Race as a structural force and driver of historic and current economic and social inequity is increasingly understood and acknowledged. But most people in the United States still think that “race” is an urban issue. Too few grasp that one in four rural people are people of color, and that they, along with immigrants from many nations, now account for the bulk of rural population stabilization or growth.

The connection of race to place and class in rural areas cannot be overlooked: Outside of central Appalachia, the vast majority of the rural persistent poverty counties noted above are overwhelmingly communities of color – Black, Latinx, Native, and many immigrant people. Overall, rural populations of color suffer higher poverty rates than their urban counterparts. In short, for rural and Native communities, place and class discriminatory practices have only deepened the historic grip and impact of racial discrimination on economic, health, and social inequality.

What does this have to do with measuring rural success?

First, from a process standpoint, it calls for policy and investment designers to compare the place, class, and race profile of the places and initiatives they support versus the ones they miss; to analyze if it may be due to preferences embedded in their scoring or criteria for funding; and to conduct special design for and outreach to the “unreached rural” in every region, race, and class.

Second, to change decisions and design, it calls for rural communities and organizations themselves, as well as foundations, government, and private grantmakers and investors, to diversify (and measure) the composition of their decision-making groups to include rural leaders, rural low-wealth people and communities, and rural Black, Native, Hispanic, and immigrant people – as a critical step toward dismantling practices that have created and deepened wealth and social inequality within rural and between rural and urban places and populations.

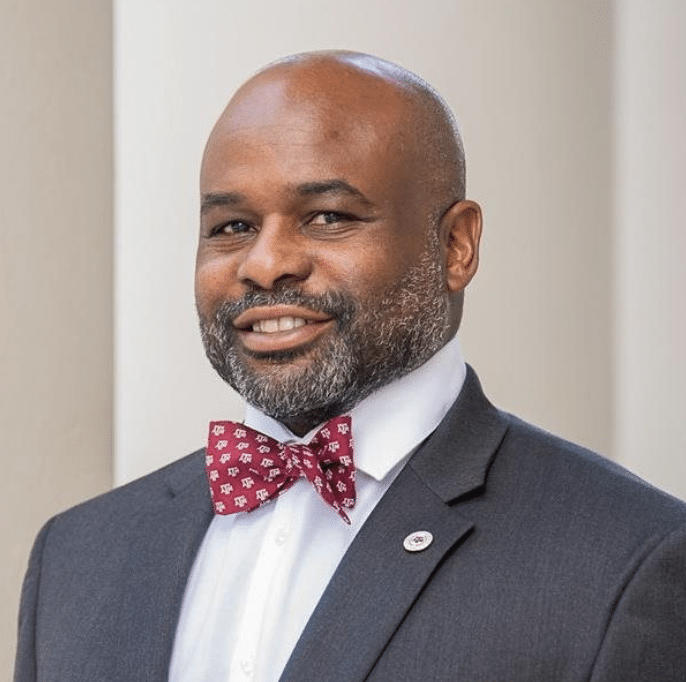

As one TRALE participant, John Cooper, Jr. of Texas A&M’s Institute for Sustainable Communities, put it:

“The outcome is the quality of the strategies, but it’s also the quality of the process, so there’s procedural equity in everything we do. We want to make sure that the teams that we put together to work on plans are representative of the places we’re working. So, we want the movers and shakers, but we also want the moved and the shaken, right? The people who stand to be most impacted by the work we do – we come to them as co-learners, as partners, and we see them as leadership assets in the places that we work.”

John Cooper Jr, Texas A&M University

Lastly, it calls for consistently measuring decreases in inequity – across race, place, and class, both within our rural communities and Native nations, and between rural and urban places and populations – as a standard outcome that indicates progress toward rural prosperity. Measuring equity requires absolute measurement (the aggregate increase in financial wealth, for example) and relative measurement, such as a change in the gap between Black and white median household income or high-wealth and low-wealth households in a rural place, or between rural and urban in a region or state. Decreases in these economic, social, and cultural divides are essential to strengthen both rural and national prosperity.

“It’s really important that jobs are year-round with wages and benefits that support a family within the cost structure of the community we live in. I don’t think that’s always captured in the economic reports, nor in the criteria shaping federal programs. Too often these focus on appreciation of household wealth or income, not locally generated wages, and this appreciation is often driven by a lot of other revenue. This is creating real distortions – and much greater inequality – in our community between the year-round residents who live and work here and other residents who have only recently bought homes.”

Nils Christoffersen, Wallowa Resources

“To us, rural is a culture, and when we define it as a culture and make it a topic around equity, I think it’s harder to marginalize rural people in rural places. [A] huge part is just ensuring that people understand who we are and that we have representation in those different buckets – to not only see our successes and see our wins, but to understand how to digest our data and make it a story that’s positive and not weaponize it against us.”

Justin Burch, Delta Compass

“The Latinx community is 85% of the county population, unemployment can be as high as 30%, and some of the challenges that we have around health and environmental conditions are due to the toxic seabed that we have here that has been collecting fertilizers and pesticides from agriculture. We have a booming agricultural industry, but now that the Salton Sea is drying up, it has exacerbated the existing health challenges in the county – one in five children have asthma, and we’re number one in the U.S. for diabetes deaths. We are working with the smaller communities that are adjacent to the Salton Sea… helping them have a stronger voice and visibility, because basically they feel they have no voice.”

Roque Barros, Imperial Valley Wellness Foundation

“In the WealthWorks model, we know that the ‘who’ matters, and that livelihoods and ownership matter. So, are we measuring the number of employee-owned enterprises in the region versus just businesses? Yes! We measure the number of social advocacy agencies in a region that helped create social capital and build social capital and cultural capital based upon NAICS codes. Instead of earnings, we measure wage gaps. Gender wage gaps, racial wage gaps – how about we measure that instead of just the amount that people are making?”

Cheryl Hills, Region Five Development Commission

“Any time we define what success is for somebody else – I find that problematic. So one of the things that I’m impressed with, coming from the state government into a Community Action Agency, is that a good portion of the Agency Board of Directors is made up of the clients who we serve. This enables us to empower them and place them in decision-making positions. I believe that is important.”

Douglas Beard, Northern Kentucky Community Action

Recommendations

Government

- Measure yourself first. Assess the distribution of grants and investments. Regularly analyze and compare the economic, place, and race demographics of where your funding or lending is going – and is not going. If there is an uneven distribution in some rural areas or populations, evaluate the reasons why. The “left-out” are organizations, communities, and businesses that do not compete successfully for funding, or that do not apply at all because of the complexity, often tied to internal processes, or the small size of the pool of dollars, and smaller and more remote. They can easily fall off the radar screen of program designers.

- Check for equity bias in application procedures and funding requirements and expectations. Look carefully at eligibility requirements. Are thresholds causing rural areas or pockets that are not accessing development resources, innovation, or program design to reach the “left-out”?

- Ask for equity process indicators and measures. Effective planning to reduce inequity requires seats at the table not just for the more obvious stakeholders but also for the underrepresented. A process that includes broad rural place, class, race, and cultural representation can surface inequities in opportunity access and outcomes.

- Ask grantees and awardees to measure changes in inequity. Increasing prosperity for more people and reestablishing a strong middle class must be accompanied by decreases in economic, race, and place divides – in relation to wealth, health, housing, civic engagement, and decision-making voice and influence, among other factors.

- For disaster-related funding, seek ways to measure that the most vulnerable rural populations and rural areas with the least capacity have prevention and preparedness procedures in place in advance, and are addressed at the same time as (or before) well-to-do areas during remediation.

Philanthropy

- Everything in the Government section, plus:

- Support the creation and maintenance of national, regional, or local civic leadership diversity databases. Where technical and geographic expertise exists, invest to help reveal and make visible where inequities and inequity persist.

- Support methods and pilots for analyzing and measuring equity in rural places. Taking on how to measure decreases in inequities – and increases in equity – across rural regions can help facilitate that measuring and bring attention to its importance.

Rural Practitioners

- Know your local equity baseline. Estimate what the particular equity – or inequity – conditions and challenges are in your place and community. In relation to class, race, place, gender, age, or other factors, how does the current status of different assets or conditions in your place compare to the population demographics in your community, or how does your community compare to the region, the state, or the country?

- Ask the “reducing/increasing equity” question whenever you design a project or program. Typically, when you think about it at the start of a project, you can design and implement almost any project or initiative in a way that increases equity or in a way that either worsens or maintains inequity. If you ask at the start, “How can we do this in a way that also increases fair opportunity and equity?”, you are more likely to do so – especially if you choose a goal and an indicator.

- Evaluate equity conditions within your own organization. Recognize, have a dialogue, and act on embedded conditions that inhibit diversity, equity, and participation in your staffing, volunteers, and decision-making.

- Work toward diversity in local decision-making positions. Where elected or appointed representation does not reflect the demographics – locally or statewide or in your region, whether in elected offices, agency appointments, boards, commissions, or town festival committees – cultivate and advocate for more inclusive civic leadership. Document changes in this leadership over time so that the community can see progress or movement of any kind.

Learn more about dismantling discriminatory practices that affect rural people, places, and economies with the Thrive Rural Framework. This tool outlines the building blocks needed to achieve rural prosperity. It addresses the unique types of systemic discrimination due to race, place, and class that people in rural communities and Native Nations face.

Action Story 4: The Value of Access and Participation for Equity

Moving toward equity requires shifting – and measuring shifts in – race, place, and class divides, including in terms of access to systems.

Jennie Stephens, executive director of the Center for Heirs’ Property Preservation in South Carolina, tells what happens when expanding (and measuring) access is a priority: “Forestry is a $21 billion industry in South Carolina, but there are very few people of color who are either working or connected to the industry. What we were able to do was to create a system that allowed people of color to access the forest industry. It was a public-private partnership, so you have the nonprofit who’s the trusted organization in the community, who then invited in funders or representatives of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). We know about USDA and people of color; it’s not been a good relationship in the past. And so the ability to create a system so that people of color would learn about forestry, know the resources, know that there was a forestry association, or know that there were funds available from USDA, increased the number of local people of color who are now engaging in forestry enterprises.”

The work has had numerous – and measurable, though not always counted – equity outcomes beyond the family wealth-building and environmental stewardship benefits, according to Stephens. “My board chair, who is a participant in our sustainable forestry program and is a retired principal, just sent me a video in which the USDA Natural Resource Conservation Service (RCS) recorded and used her as their spokesperson. We have landowners who are serving on national committees for forestry, or in our state. So, the fact is that, yes, they’re generating more money because income is important. But there are also those intangibles where they’re able to be invited to tables that they would not normally be invited to sit around because (1) they didn’t know the table exists, and (2) the people who were already at the table didn’t know how to access them.” Measuring the increase in access to and influence in systems that generate wealth and prosperity is as important as measuring any resulting wealth itself.

Measurement Principle 5: Identify, value, and measure effective collaboration as progress toward rural prosperity.

The proverb goes: if you want to go fast, go alone; if you want to go far, go together. To make significant progress on rural community and economic development and health issues, it is likely that you can only ever get “there” if you go together. In essence, going it alone is rarely even an option.

When a big challenge or opportunity arises (or persists), a rural organization can only do so much by itself. Likewise, an individual rural community can rarely make solo progress on an issue or opportunity when it really affects an entire region, as does, for example, the potential opening or closing of a significant area business, the availability of hospital and medical services, road quality, internet coverage and standards, or the presence and affordability of childcare slots. The impact of any of those is important to multiple communities and populations in a rural region, so addressing it must call on their multiple assets and abilities for effective action.

Collaboration across organization and place requires a sturdy organizational framework for acting together. Partly due to greater density and proximity, these tend to be more natural or common in metro than in rural areas – for example, metropolitan transportation authorities, regional business associations, active councils of government, or metro education and workforce consortia. In rural places, neighboring jurisdictions are further apart, the tax base that might be tapped to work together is small or nonexistent, and large institutions that might pull together or anchor regional cross-sector collaboration – like universities, hospitals, or major foundations – are scarcer. There is no government of the region, no shared financial resource base to invest together, and no one with the responsibility to analyze the geographic range of an issue, bring people together, and make decisions for action.

TRALE participants underlined that rural community and economic development actors essentially have to make the case for the importance of these functions – and then invent how they are organized and where they sit; otherwise, individual organizations or communities in a given region may end up working at cross purposes or simply not have the capacity or resources to make enough difference. Where they do succeed, they take on the qualities of a Rural Development Hub, a role played by different types of organizations in different rural places (e.g., community action agencies, community foundations, community development financial institutions, colleges, free-standing regional non-profits, chambers of commerce, among others). Regional councils of government or economic development districts, which draw support from member municipalities, the U.S. Economic Development Administration, and some states, can also foster regional collaboration and action.

In short, when it comes to advancing economic and community development, rural efforts typically have greater impact when they involve networking and working together across organization and place. Collaboration is particularly critical across low population density and lower-wealth regions in order to leverage resources and build critical mass for project implementation.

However, effective collaboration typically takes more time and effort than going it alone. In rural, collaboration multiplies in complexity due to distance, fewer organizations or local governments with sufficient paid staff whose jobs can support it, and things as “simple” as poor internet connectivity. Practitioners in the TRALE made this point repeatedly: Collaboration is critical to progress, and it is rarely supported financially.

Yet, as Ta Enos, CEO of Pennsylvania Wilds, put it, the effort to collaborate can make the most difference over time in advancing toward better rural futures in a region:

“The partnerships we’ve built across municipal boundaries, different industries, and the public and private sector have been transformational. They’ve allowed our region to accomplish things together that we never could have alone. The importance of relationships, of building trust, of meeting with people face-to-face so they know who you are and what you’re about and that you respect them enough to listen, cannot be understated in a rural area. You have to take the time to show up, literally, or it won’t work. Partnership work is never done, and it takes real resources to do it well.”

Ta Enos, PA Wilds Center

Other key points included:

- More funders are beginning to understand the importance of collaboration, and some even now require it. But few support what it takes to do it, especially the extra effort and cost it takes in rural places.

- When a rural collaboration is supported by multiple funders, they rarely collaborate themselves to reduce the (often conflicting) paperwork and reporting burden for the rural collaborative.

- Sometimes collaboration exists only “on paper,” designed to meet the funders’ definitions of collaboration; this may either (a) not be the collaboration that is needed for the particular project, or (b) be represented as a collaboration by some applicants via local endorsement letters and the like, but not play out in reality.

What does this have to do with measuring rural development progress toward success? The TRALE process suggests that effective collaboration is critical for steady progress toward wider and deeper prosperity. But “effective” requires that the collaboration must be built on real relationships, shared understanding and goals, broad participation and decision-making across community and population stakeholders, established methods and structures for working together, and leveraging resources – all in ways that can set the rural area up for even more progress in the future. These can be measured, as evidenced by assessments of collective impact and similar efforts. Surely there is much work to be done to facilitate and design good ways to measure aspects of collaboration. But to advance toward greater and more widespread rural prosperity, it is work that must be done.

“Take Chicago, there’s a popular workforce collaborative and there’s been a lot of dollars that have been invested in that collaborative to get all the different stakeholder buckets working together and they have established common metrics and ways of sharing that data. We just don’t see that investment in a lot of rural places.”

Justin Burch, Delta Compass

“Are anchor institutions collaborating at all? Are they doing things in partnership or is everyone just sort of doing their own thing? One thing that we constantly hear from communities – and where we start to see the magic actually start to happen – is when communities say, ‘Wow! Our local government never really had any strong connection with our schools or our business community or this sector.’”

Deb Martin, Great Lakes Community Action Partnership

“[In rural America] nobody has the resources to go it alone. One of the

John Molinaro, Appalachian Partnership

things it takes to do better – that almost no funding streams are willing to pay for – is collaboration. They’re willing to pay for that particular project, but the glue that holds it all together is just probably the most difficult piece to find support for in rural communities.”

Recommendations

Government